ALAIN DE LILLE (Alanus ab/de Insulis) was born in

Lille in Flanders sometime before 1128. Though not much is known

of his personal life, Alain was a highly-reputed theologian who

taught in the famous Paris schools, and attended the Third

Lateran Council of 1179, an ecumenical council that repaired the

breach in the Church caused by the schismatic election of

antipope Callistus III. The Council, called by Pope Alexander

III, instituted legal reforms to prevent such an incident from

happening again. It also addressed issues arising out of the

heretical Waldensians and Cathars. From Paris, Alain eventually

lived and taught in Montpellier (which is why he is sometimes

called Alanus de Montepessulano). Towards the end of his

life he retired to the Cistercians in Citeaux, and it was there

that he died sometime in between 1202-03.

His

Plaint of Nature is

a genre of literature called Menippean satire (from the

Greek Cynic and satirist Menippus or Menippos of Gadara fl. 225

B.C.), and it is a combination of both prose and verse. The main

argument of the Plaint is

the writer's complaint of his contemporaries' contempt for the

natural law. He is particularly upset at the disrespect for

nature shown by homosexuality, which he sees rampant in society,

and which he sees as symbolic of the intellectual, spiritual and

moral infertility that has also infected society. As if seized

by a trance, the writer enters a dream-like state, and a

beautiful maiden,--a personification of Nature--visits him. She

is beautiful, but she shows signs of great grief, and she shares

with the dreaming poet the reasons why. Her garment is rent

because man has appropriated to himself parts of her that he has

no right to. Everywhere man acts against Nature, and, as a

result, justice has disappeared, and crime and fraud everywhere

abound. There is no more law, and man, from the dignity of

rationality where Nature has placed him, has reached the nadir

of irrationality. Though the vice of lust is everywhere

prevalent, by disregarding Nature man also suffers from other

vices, which Nature discusses with the poet. She shares with the

poet some remedies to such vices in the forms of maxims. Then,

during the course of the dream, comes Hymenaeus,

representative of Christian marriage, and following close behind

him, the virtues:

Chastity, Temperance, Generosity, and Humility. Towards the end of the

dream, Genius appears, and Truth, the daughter of

Nature and Genius, shows herself opposite Falsehood, who is

bald, and exceedingly ugly and rattily dressed. Eventually, the

poet awakes from his trance-like state. The De

Planctu Naturae begins

with verse, as the poet expresses his sorrow at how Nature is

disregarded by the mores of his time, most notably in the

disregard of Nature in the area of sexual behavior.

|

In lacrymas risus, in fletum gaudia verto:

In

planctum plausus, in lacrymosa jocos,

Cum sua

naturam video secreta silere,

Cum Veneris monstro

naufraga turba perit.

Cum Venus in Venerem

pugnans, illos facit illas:

Cumque suos magica

devirat arte viros. |

I turn from laughter to tears, from joy to grief,

from merriment to lament, from jests to wailing,

when I see that the essential decrees of Nature are

denied hearing, while large numbers are shipwrecked

and lost because of a Venus turned monster, when

Venus wars with Venus and changes "hes" into "shes"

and with her witchcraft unmans man.

|

|

Heu! quo naturae secessit gratia? morum

Forma, pudicitiae norma, pudoris amor!

Flet natura, silent mores, proscribitur

omnis

Orphanus a veteri nobilitate

pudor. |

Alas! Where has Nature with her fair

form betaken herself?

Where have the

pattern of morals, the norm of chastity,

the love of modesty gone?

Nature

weeps, moral laws get no hearing,

modesty, totally dispossessed of her

ancient high estate, is sent into exile.

|

What is the cause of the poet's lamentations?

"The active sex shudders in disgrace as it sees

itself degenerate into the passive sex." Activi

generis sexus, se turpiter horret, sic in passivum

degenerare genus.

"Becoming a barbarian in grammar, he

disclaims the manhood given him by nature." Se

negat esse virum, naturae factus in arte Barbarus.

"No longer does the Phrygian adulterer [i.e., Paris]

chase the daughter of Tyndareus [i.e.,

Helen of Troy], but Paris with Paris performs unmentionable and monstrous

deeds." Non

modo Tyndaridem Phrygius venatur adulter, sed Paris

in Paridem monstra nefanda parit.

"The little cleft of Venus has no charm for him," huic

Veneris rimula nulla placet.

According to Alain, rejection of the natural role of

man and woman, beginning in the area of the use of

sexual faculties, is a rejection of the natural law,

and with it the rejection of the one true God. It is

a lapse into moral, intellectual, and spiritual

darkness. It robs mankind of his Genius.

|

A Genii templo tales anathema merentur,

Qui Genio decimas, et sua jura negant. |

Men like these, who refuse Genius his

tithes and rites,

deserve to be excommunicated from the

temple of Genius.

|

The invocation of "Genius" by Alain is intended to

show the intricate relationship between

homosexuality, the loss of reason, and the ultimate

infertility in thought that results from an

acceptance of such a vice as right, whether de

facto or de

jure.

Etymologically, the word "genius" is related to

gignere, to

bring forth, to give birth to (Sheridan, 59-60).

The word genius was frequently linked with the Greek

word "daimon"

(δαίμων), a lesser god, guiding spirit, or tutelary

deity, unique to each man. The daimon,

made famous by Socrates who followed it to his

death, was, perhaps, the pagan precursor to the

notion of a guardian angel.

Winged

Genius from villa of P. Fannius Synistor in

Boscoreale, near Pompeii. Winged

Genius from villa of P. Fannius Synistor in

Boscoreale, near Pompeii.

The linkage of this intellectual component to the

generative component in the notion of Genius may be

seen in a fragment of Valerius Soranus that has been

preserved by St. Augustine in his De

Civitate Dei. Soranus

describes a Genius as "a God who is in charge of,

and has power over, the birth of all things." De

civ. Dei, 7.13

(Quid est Genius?

"Deus, inquit, qui praepositus est ac vim habet

omnium rerum gignendarum.") Likewise, St.

Isidore in his Etymologiesdescribes

"Genius" so as to make the relationship between

intellectual and procreational fertility even more

apparent. "They give him the name of Genius because,

so to speak, he has power over the birth of all

things, or from the fact that he brings about the

birth of children. Thus the beds prepared for the

newly-wed husband, were called 'genius' couches." Etym., 8.11.88-89

(Genium autem

dicunt, quod quasi vim habeat omnium rerum

gignendarum, seu a gignendis liberis; unde et

geniales lecti dicebantur a gentibus, qui novo

marito sternebantur.) Genius, then, had a

double duty. It was charged with keeping the human

race in existence, both in his body and in his

spiritual soul. In assuring both the spiritual and

the physical fertility of mankind. Genius was seen

as intricately bound to Nature; indeed, Genius was

Nature's great high priest.

It can easily be seen that Genius has a very

close kinship with Nature, particularly with

Nature as described by Alan in the De

Planctu. Both have the same

interests--that like shall produce like, that

sexual relations shall follow the norms of

Nature, that those born shall grow up to live a

life in accord with Nature as understood by

right reason, that the human race shall not die

out. Nature may well call Genius her other self.

Genius gives the final form to the things of

Nature.

Sheridan, 61-62. One wonders whether Genius has

departed from any country that has adopted

homosexuality as a fundamental legal right, or has

signed the United Nations declaration on sexual

orientation and gender identity. Have we been

excommunicated from the temple of Genius? Along with

Alan of Lille, we have cause to issue our modern

Plaint:

In lacrymas risus,

in fletum gaudia verto:

In planctum plausus, in lacrymosa jocos,

Cum sua naturam video secreta

silere . . .

*Sheridan refers to James J. Sheridan,

trans., Alan of Lille: The Plaint of Nature

(Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies,

1980). Translations of Alan of Lille's De

Planctuare taken from this text.

NATURE IS LOVELY AS SHE APPEARS in Alan of

Lille's The

Plaint of Nature when

the poet falls into a trance, a dream-like state

while reciting his elegy at his fellows'

rejection of Nature's guidance, especially in

the area of the sexual faculties. Everywhere he

sees abuse, a bad grammar and bad logic in sex,

which manifests itself in a rejection of the

human dignity and genius, and ultimately leads

man into irrationality, a perverse sex

transmutes itself into perverse thought. Corruptio

optimi pessima. The

poet is privileged to see Nature as she is, as

she glides down from the inner palace of the

impassible world. She contains the entirety of

the cosmos cap-a-pie,

from head to foot, galaxy to worm.

She comes from the heavens in a chariot

of glass that is drawn by doves--Juno's

birds. Above her was reason, appearing as a

man above her head, and who gives her

guidance as she steers the crystal chariot

towards the entranced poet. Her beauty was

too much for him:

When I was concentrating

my rays of vision or, if I may say so,

the troops of my eyes, to explore the

glory of this beauty, my eyes, not

daring to confront the splendour of such

majesty and dulled by the impact of

brilliance, in excessive fear, took

refuge in the war-tents of my eyelids.

Ad cujus contemplandam pulchritudinem

dignitatis, dum tanquam manipulos,

oculorum radios conlegarem visibiles,

ipsi tantae majestatis non audentes

obviare decori, splendoris hebetati

verberibus, nimis meticulosi ad

palpebrarum contubernia refugerunt.

She is resplendent as the ideal. Nature is

the ideal of

which the individual things in nature are

the individuation. As the ideal she

possesses what appears to be a slate tablet

upon which she calls up images with a

clerk's stylus, which fade in and fade out,

in a constant birth-and-death cycle, always

striving for the ideal, yet never quite

capturing it in

toto.

In lateritiis vero tabulis arundinei

styli ministerio, virgo varias rerum

picturales sociabat imagines; pictura

tamen subjacenti materiae familiariter

non cohaerens, velociter evanescendo

moriens, nulla imaginum post se

relinquebat vestigia. Quas cum saepe

suscitando puella crebro vivere

faciebat, tamen in scripturae proposito,

imagines perseverare non poterant.

When she neared, it was as if

the visible world celebrated her coming. The

firmament shone, the day turned bright, the

moon became unnaturally brilliant. The air,

the sea, and all the creatures they

contained paid obeisance as it were, to the

paradigm or exemplar of their nature. The

earth and its inhabitants turned fruitful in

her presence: "Thetis, too, marrying Nereus,

decided to conceive a second Achilles." Thetis,

etiam nuptias agens cum Nereo, Achillem

alterum concipere destinabat. The

naiades (water nymphs), the hamadryades

(tree nymphs), and the napaeae (nymphs of

the wooded vales) sprung forth from the

streams, the trees, and the valleys of the

earth to present the coming Nature with

their various gifts, not to be outdone by

the animals of the land. The world, as it

were, experienced a re-birth, a new Spring,

at Nature's coming. "Proserpine, disdaining

the marital bed of the lord of Tartarus,

returned to her home in the upper world,

refusing to be cheated of a face-to-face

meeting with her mistress." Proserpina,

toro mariti fastidito tartarei, ad superna

repatrians, suae imperatricis noluit

defraudari praesentia.

Thus everything in the

universe, swarming forth to pay court to

the maiden, in wondrous contest toiled

to win her favour.

Sic rerum universitas ad virginis fluens

obsequium, miro certamine laborabat sibi

virginis gratiam comparare.

Nature has as it were an aura, a halo, which

shines around her and gives evidence of her

supernatural origin. She bears the image,

the likeness, the vestige of the God who

created her, and so she shows the

supernatural origins of her nature, the

light, non

similitudinarie radiorum repraesentans

effigiem,not presenting an image of

light rays by resemblance, sed

eorum claritate nativa naturam praeveniens, but

with that native clarity that precedes, that

is, surpasses, the natural. Her head appears

a virtual star-cluster, in

stellare corpus caput effigiabat.

Nature has a white, cruciform headband,

which separates her lovely hair, which is

held in place with a comb of gold that

blends into her golden hair.

Her

visage is the epitome of balance, of

harmony, and of beauty. A lovely forehead,

and brows, "starlike in their golden

radiance, not thickened to bushiness nor

thinned to over-sparseness, enjoyed a mean

between both extremes," aureo

stellata fulgore, non in silvam evagantia,

nec in nimiam demissa pauperiem, inter

utrumque medium obtinebant. Here

eyes like stars; her nose "neither unduly

small nor abnormally prominent," nec

citra modum humilis, nec injuste prominens;

her mouth, her lips, her teeth, her cheeks .

. . all that which composed her face, both

in color and in form, "showed the effects of

a harmonious mixture," sentiebat

temperiem. As

God's creation, she is the epitome of

harmony: ratio

ordinis.

This harmonious

balance is not limited to her countenance,

and her body shares in it, as the poet in

his trance describes seriatim Nature's

neck, her shoulders, her breasts, her arms,

her flanks, all bear the "stamp of due

moderation," justae

moderationis impressa sigillo, and

"brought the beauty of her whole body to

perfection," totius

corporis speciem ad cumulum perfectionis

eduxit. She

is, in fine, altogether desirable in the

beauty of her harmony, and in the harmony of

her beauty. The poet implies that one would

have to be a fool to shun her, not to desire

her. And this just based upon her external

features, for what realities she contained

within her were sure to be more beautiful

than what he saw:

Caetera vero quae

thalamus secretior absentabat, meliora

fides esse loquebatur.

As for the other things which an inner

chamber hid from view, let a confident

belief declare that they were more

beautiful.

Patently apparent, Nature,

though alluring, was wholly chaste in her

fruitfulness. But though great her beauty,

she bore the tears of sorrow, traces of the

injuries she received at the hands of men

who, despite her desirability, had abandoned

her.

Nature was crowned with the

aeviternal cosmos, with its recurring,

circular paths, resplendent with jewels,

representing the stars, all revolving around

the fixed polar stars, and the

constellations of the Zodiac: Leo, Cancer,

and Gemini, with a certain pride of place,

followed next in groups of threes, by

Aquarius, Capricorn, and Sagittarius,

Taurus, Aries, and Pisces, Virgo, Libra, and

Scorpio: and the constellations without

Zodiac, or part in part out, were also

there. Below the Zodiac jewels of twelve

organized in sets of three were other

jewels, a set of seven, "forever maintaining

a circular motion, in a marvellous kind of

merriment busied themselves with a

verisimilar dance,"motum

circularem perennans, miraculoso genere

ludendi, choream exercebat plausibilem. Saturn

was a diamond; Jupiter, an agate; Mars

asterite; Venus sapphire, Mercury amethyst;

the Sun a ruby, and the Moon a waxing and a

waning pearl.

Nature's dress was a

changing coat of many colors, multifario

protecta colore, as

it went from white, to red, to green. It was

decorated with the birds of the air: the

eagle, the hawk, the kite, the falcon, the

heron, the ostrich, the swan, the peacock,

the phoenix, the stork, the sparrow, the

crane, the barnyard cock, "like a common

man's astronomer, with his crow for a clock

announces the hours," tanquam

vulgaris astrologus, suae vocis horologio,

horarum loquebatur discrimina. The

wild cock, the horned and the night owl, the

crow, the magpie, the jackdaw, the dove, the

raven, the partridge, the duck and the

goose, the turtle-dove, the parrot, the

quail, the woodpecker, the meadow-pipit, the

cuckoo, the swallow, the nightingale, the

lark, all with their unique traits and

features, and finally the bat, "a

hermaphrodite among birds, held a zero

rating among them," vespertilio

avis hermaphroditica, cifri locum inter

aviculas obtinebat.

Haec animalia, quamvis

illic allegorice viverent, ibi tamen

esse videbantur ad litteram.

These living things, although they had

there a kind of figurative existence,

nevertheless seemed to live there in the

literal sense.

Nature also in a lovely shroud of muslin,

that faded from white to a sea-like green,

and contained in the middle portion, images

of the creatures of the sea: the whale, the

seal, the sturgeon, the herring, the plaice,

the mullet, the trout, salmon, and dolphin,

the sirenian. And lower down on this robe

were the fresh water fish: pike, barbel,

shad, lamprey, eel, perch, chub . . .

These figures,

exquisitely imprinted on the mantle like

a painting, seemed by a miracle to be

swimming.

Hae sculpturae, tropo picturae,

eleganter in pallio figuratae, natare

videbantur pro miraculo.

Nature was clothed in tunic, embroidered

with the beasts and creatures of the earth,

above all man.

On the first section of

this garment, man, divesting himself of

the indolence of self-indulgence, tried

to run a straight course through the

secrets of the heavens with reason as

charioteer.

In hujus vestis parte primaria, homo

sensualitatis deponens segnitiem, ducta

ratiocinationis aurigatione, coeli

penetrabat arcana.

But this part of Nature's tunic was rent,

torn, showing the effects of contumely and

injury. Only man, it seems, can injure and

offend Nature, as the other parts of this

robe, which bore the other animals, was not

so torn. "In these a kind of magic picture

made land animals come alive," in

quibus quaedam picturae incantatio,

terrestria animalia vivere faciebat.

So the elephant, the camel, the buffalo, the

bull, oxen, the horse, the ass, "offending

our ears with his idle braying, as though a

musician by antiphrasis, introduced

barbarisms into music," clamoribus

horridis aures fastidiens, quasi per

antiphrasim organizans, barbarismum faciebat

in musica. There

also the unicorn, the lion, the bear, the

wolf, the panther, the tiger, the wild ass

and the tame, the boar, the dog, the stag

and doe, the goat, the ram and his harem of

ewes, the fox, the hare and his cousin the

rabbit, the squirrel, beaver, lynx, marten,

and sable.

Though hid from his sight,

the poet surmised that the undergarments and

shoes contained the vivid imagery of the

herbs and trees, with their four-fold colors

corresponding to the four-fold seasons, and

the flowers: the rose, the thyme, the

Narcissus, the columbine, the violet, the

arbutus, the basilisca . . .

|

Hae sunt veris opes, et sua

pallia,

Telluris species, et

sua sidera,

Quae pictura suis

artibus edidit,

Flores

effigians arte sophistica.

His florum tunicis prata

virentibus

Veris nobilitat

gratia prodigi.

Haec byssum

tribuunt, illaque purpuram;

Quae texit sapiens dextra

favonii. |

These are the riches of Spring

and her barb,

The beauty of

earth and its stars;

These

the picture brought forth by its

powers,

Giving an image of

flowers by a skillfully

deceptive art.

Spring, lavish

in favours, ennobles the meadows

With these garments of flowers

in bloom.

These meadows give

linen, these others give purple

When the zephyr's right hand has

clothed them. |

And it was then that Nature began to

speak . . .

NATURE’S BEAUTY WAS AFFLICTED,

afflicted by sorrow, and no amount

ofencomia by

the creation of which she was the

foster mother (nutricis

familiari) or deputy of the

Creator God (Dei

auctoris vicaria) could

assuage it. The poet, unaccustomed

to the purity of Nature’s ideal,

swoons in delirium, a state of

ecstasy between life and death.

Nature, however, raised the poet up

and strengthened the poet, and spoke

to the poet in words archetypal, as

if she spoke to him in the realm of

the Ideal.

When she realized

that I had been brought back to

myself, she fashioned for me, by

the image of a real voice,

mental concepts and brought

forth audibly what one might

call archetypal words that had

been preconceived ideally.

Quae postquam

mihi me redditum intellexit, in

mentali intellectu materialis

vocis mihi depinxit imaginem,

cum quasi archetypa verba

idealiter percontexta, vocaliter

produxit in actum.

Nature chastises our poet, severely

yet gently, for having ignored her

in his musings, thereby clouding up

his mind, defrauding his reason, and

banishing her from his memory. It is

as if Nature informally sues the

poet in a series of complaints,

framed under one big cause of action

Why?

Why do you force

the knowledge of me to leave

your memory and go abroad, you

in whom my gifts proclaim me who

have blessed you with the right

bounteous gifts of so many

favours?

Cur a tua memoria mei facis

peregrinari notitiam, in quo mea

munera me loquuntur, quae te tot

beneficiorum praelargis beavi

muneribus?

Who, acting by an

established covenant as the

deputy of God, the creator, have

from your earliest years

established the appointed course

of your life . . .

Quae a tua ineunte aetate, Dei

auctoris vicaria, rata

dispensatione, legitimum tuae

vitae ordinavi curriculum?

Who, of old brought your

material body into real

existence from the mixed

substance of primordial matter .

. .

Quae olim tui corporis

materiam adulterina primordialis

materiae essentia fluctuantem,

in verum esse produxi?

Who, in pity for your

ill-favoured appearance that

was, so to speak, haranguing me

continually, stamped you with

the stamp of human species and

with the improved dress of form

brought dignity to that species

when it was bereft of adornments

of shape?

[Quae] cujus

vultum miserata deformem, quasi

ad me crebrius declamantem,

humanae speciei signaculo

sigillavi, eamque honestis

figurarum orphanam ornamentis,

melioribus formatis vestibus

honestavi?

What sort of ingrate is man, that he

forgets that Nature gave him his

senses to protect him? That he

forgets how well she him “adorned

with the noble purple vestments of

nature,” totius

corporis materia nobilioribus

naturae purpuramentis ornate,

so that his body might, in a union

analogous to marriage, join with the

spirit in a sort of conjugal

harmony? “I have blessed both parts

of you,” Nature reminds man, but

with a caveat:

But just as the

above-mentioned marriage

[between body and spirit] was

solemnized by my consent, so,

too, at my discretion this

marital union will be annulled.

Sicut ergo

praefatae nuptiae meo sunt

celebratae consensu, sic pro meo

arbitrio, eadem cessabit copula

maritalis.

It is this marriage-like union

between man’s spirit, his intellect,

his reason, and his body that comes

undone when Nature is not followed.

And so it is that disobedience to

Nature introduces a cacophonous

divorce between the body and the

spirit, and causes the mind to be

darkened as the body pursues its

unnatural loves. The poet's

complaints against the sterile,

homosexual love that prevailed

around him, and with which the Planctus started,

had already noticed the divorce

between reason and desire.

Nature continues to expand on

how man fits into the entirety of

the cosmos, for her role with regard

to man is not limited to the giving

of his form, to the union between

the spirit and matter, so uniquely

his. She has also fitted him within

the context of the greater

macrocosmos. He is indeed, a

microcosmos, a world in miniature.

The macrocosmos is man writ large.

There is an analogy between man and

the cosmos. In a way, the one is in

the other.

For I am the one

who formed the nature of man

according to the exemplar and

likeness of the structure of the

universe so that in him, as in a

mirror of the universe itself,

Nature’s lineaments might be

there to see.

Ego sum illa,

quae ad exemplarem mundanae

machinae similitudinem, hominis

exemplavi naturam; ut in eo

velut in speculo, ipsius mundi

scripta natura appareat.

Within himself, man experiences the

same stresses as the cosmos:

For just as concord in discord,

unity in plurality, harmony in

disharmony, agreement in

disagreement of the four

elements unite the parts of the

structure of the royal palace of

the universe, so too, similarity

in dissimilarity, equality in

inequality, like in unlike,

identity in diversity of four

combinations bind together the

house of the human body.

Sicut enim quatuor

elementorum concors discordia,

unica pluralitas, consonantia

dissonans, consensus

dissentiens, mundialis regiae

structuras conciliat, sic

quatuor complexionum compar

disparitas, inaequalis

aequalitas, deformis

conformitas, divisa identitas,

aedificium corporis humani

compaginat.

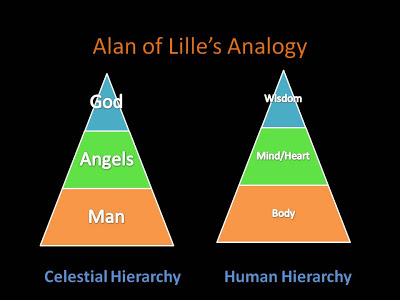

Man mimics the retrograde motions of

the planets, as he finds within

himself “continual hostility between

sensuousness and reason,” sensualitatis

rationisque continua reperitur

hostilitas. There

is in him an eternal tug of war, a

dualism, between reason and sense,

body and spirit:

|

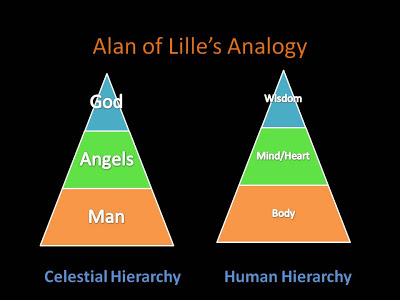

In this state [republic],

then, God gives commands,

the angels carries them out,

man obeys. God creates man

by his command, the angels

by their operation carry out

the work of creation, man by

obedience re-creates

himself. By his authority

God decrees the existence of

things, by their operation

the angesl fashion them, man

submits himself to the will

of the spirits carrying out

the operation. God gives

orders by his magisterial

authority, angels operate by

ministerial administration,

man obeys by the mystery of

regeneration.

|

In hac ergo republica

Deus est imperans; angelus

operans, homo obtemperans.

Deus operando hominem creat,

angelus operando procreat;

homo obtemperando se

recreat. Deus rem

auctoritate disponit;

angelus actione componit;

homo se operantis voluntati

supponit. Deus imperat

auctoritatis magisterio;

angelus operatur actionis

ministerio; homo obtemperat

regenerationis mysterio. |

Sheridan's translation cannot

convey the tripartite verbal order

between God, angels, and man. imperans,

operans, obtemperans; creat,

procreat; se recreat; disponit,

componit, se supponit. Man

is to follow God in a manner unique

to himself. He has been given an

active role in participation in

God's eternal order, in his eternal

law. This is what compliance with

the natural law is all about. It is

through Nature that man is created.

It is through Nature that man is

re-created. It is through Nature

that man is regenerated. This order

between God and angel and man is

also found within man himself. Hujus

ergo ordinatissimae reipublicae in

homine resultat simulacrum.

Man's

internal constitution thus mimics

the universal constitution. He is a

microcosmos. And this analogy goes

far beyond the analogy between God

and the Angelic and Human orders and

the internal constitution of man

regarding Wisdom/Mind and Heart

[Magnaminity (magnanimitas)]/Body.

"In other things, too, the form of

the human body takes over the image

of the universe." In

aliis etiam corporis humani

partibus, mundi figuratur effigies. Much

of this analogy between the cosmos

and the inner constitution of man

is, however, shrouded in secrecy,

and it goes beyond what words can

express even if the concept could be

grasped. This analogy between cosmos

and man is veiled in secrecy so that

it may not be cheapened by too

vulgar a knowledge. Nature thus

hides the secret things of God. But

man is not to think that Nature

arrogates to herself Divinity. God

transcends Nature. Nature is not

God, but under God. Man's

internal constitution thus mimics

the universal constitution. He is a

microcosmos. And this analogy goes

far beyond the analogy between God

and the Angelic and Human orders and

the internal constitution of man

regarding Wisdom/Mind and Heart

[Magnaminity (magnanimitas)]/Body.

"In other things, too, the form of

the human body takes over the image

of the universe." In

aliis etiam corporis humani

partibus, mundi figuratur effigies. Much

of this analogy between the cosmos

and the inner constitution of man

is, however, shrouded in secrecy,

and it goes beyond what words can

express even if the concept could be

grasped. This analogy between cosmos

and man is veiled in secrecy so that

it may not be cheapened by too

vulgar a knowledge. Nature thus

hides the secret things of God. But

man is not to think that Nature

arrogates to herself Divinity. God

transcends Nature. Nature is not

God, but under God.

|

But, lest by thus first

canvassing my power, I seem

to be arrogantly detracting

from the power of God, I

most definitely declare that

I am but the humble disciple

of the Master on High. For i

my operations I have not the

power to follow closely in

the footprints of God in His

operations, but with sighs

of longing, so to speak,

gaze on His work from afar.

His operation is simple,

mine is multiple; His work

is complete, mine is

defective; His work is the

object of admiration, mine

is subject to alteration. He

is ungeneratable, I was

generated; He is the

creator, I was created; He

is the creator of my work, I

am the work of the Creator;

He creates from nothing, I

beg the material for my work

from someone; He works by

His own divinity, I work in

His name; He, by His will

alone, bids things come into

existence, my work is but a

sign of the work of God. You

can realise that in

comparison with God's power,

my power is powerless; you

can know that my efficiency

is deficiency; you can

decide that my activity is

worthless.

|

Sed ne in hac meae

potestatis praerogativa, Deo

videar quasi arrogans

derogare, certissime summi

magistri me humilem

profiteor esse discipulam.

Ego enim operans, operantis

Dei non valeo expresse

inhaerere vestigiis, sed a

longe, quasi suspirans,

operantem respicio. Ejus

operatio simplex, mea

multiplex; ejus opus

sufficiens, meum deficiens;

ejus opus mirabile, meum

opus mutabile. Ille

innascibilis, ego nata; ille

faciens, ego facta; ille mei

opifex operis, ego opus

opificis; ille operatur ex

nihilo, ego mendico opus ex

aliquo; ille suo operatur

nomine, ego operor illius

sub nomine; ille, rem solo

nutu jubet existere, mea

vero operatio nota est

operationis divinae. Et ut,

respectu potentiae divinae,

meam potentiam impotentem

esse cognoscas, meum

effectum scias esse

defectum, meum vigorem,

vilitatem esse perpendas. |

(continued)

GRATIA SUPPONIT

ET ELEVAT

NATURAM, Grace

supposes and

elevates Nature.

For all

importance

Nature has as

the deputy of

God, she

recognizes that

there is a

greater reality

beyond her.

According to

reliable

testimony (fidele

testimonium),

the revealed

Word of God, man

is born by

Nature, but is

reborn by the

power of God: homo

mea actione

nascitur, Dei

auctoritate

renascitur.

Through me

he is called

from

non-being

into being,

through Him

he is led

from being

to higher

being; by me

man is born

for death,

by Him he is

reborn for

life.

Per me, a

non esse

vocatur ad

esse; per

ipsum, ad

melius esse

perducitur.

Per me enim

homo

procreatur

ad mortem,

per ipsum

recreatur ad

vitam.

Nature's

services are

"set aside," ablegatur,

in this mystery

of the second

birth,secundae

natitivatis

mysterio. These

mysteries are

beyond Nature,

beyond her ken,

her spheres of

knowledge.

Indeed, the

"entire

reasoning

process dealing

with Nature is

brought to a

standstill," omnibus

naturalis ratio

langueat.Reason

languishes. We

are at that

Wittgensteinian

point of

silence. And

where Reason

languishes,

where the words

of Nature and of

Man fails us,

Faith supplies

the means to

reach the arcane

regions of

mystery:

By the power

of firm

faith alone,

pay homage

to something

so great and

mysterious.

Sola fidei

firmitate,

tantae rei

veneramur

arcanum.

Here, again,

Nature shows a

dualism in man.

Earlier, she had

distinguished

between reason

and sensual

desire. Now she

distinguishes

between the

things of reason

and the things

of faith:

|

I

establish

truths

of faith

by

reason,

she

establishes

reason

by the

truths

of

faith. I

know in

order to

believe,

she

believes

in order

to know.

I assent

from

knowledge,

she

reaches

knowledge

by

assent.

It is

with

difficulty

that I

see what

is

visible,

she in

her

mirror

understands

the

incomprehensible.

My

intellect

has

difficulty

in

compassing

what is

very

small,

her

reason

compasses

things

immense.

I walk

around

like a

brute

beast,

she

marches

in the

hidden

places

of

heaven.

|

Ego

ratione

fidem,

illa

fide

comparat

rationem;

ego

scio, ut

credam,

illa

credit

ut

sciat;

ego

consentio

sciens,

illa

sentit

consentiens;

ego vix

visibilia

video,

illa

incomprehensibilia

comprehendit

in

speculo;

ego vix

minima

metior

intellectu,

illa

immensa

ratione

metitur;

ego

quasi

bestialiter

in terra

deambulo,

illa

vero

coeli

militat

in

secreto. |

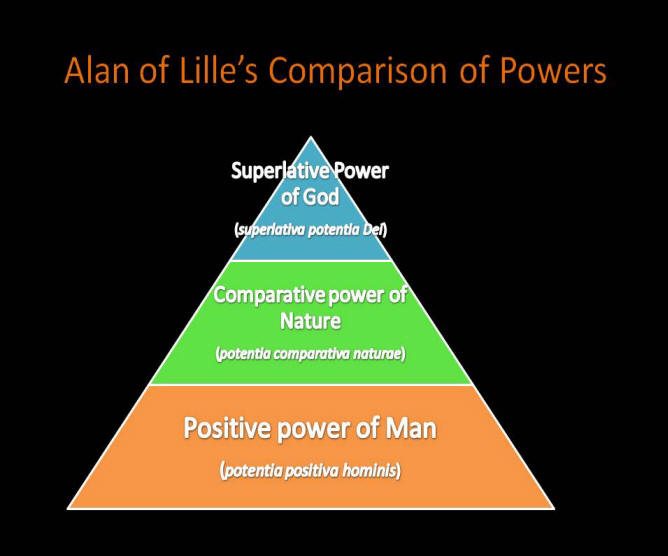

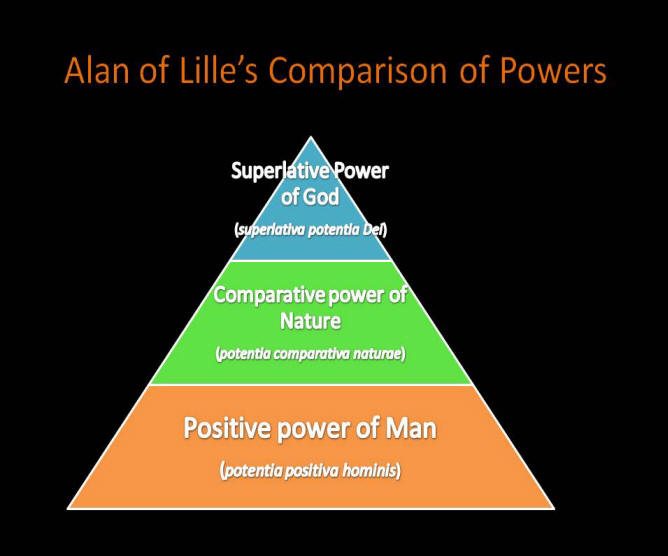

Nature then

distinguishes

three degrees of

power, tres

potestatis

gradus possumus

invenire,

in God and

Nature and Man.

God's power

is superlative;

Nature's power

is comparative;

Man's power is

positive. There

is no confusion

of powers,

though they

clearly may

cover the same

subject: man.

God's power is

preeminent,

Nature's

relatively

comparatively or

relatively

preeminent,

man's is

subordinate to

both God and

Nature. We are

not dealing here

with some sort

of Spinozan

pantheism. There

is nothing of

the sort of the Deus

sive Natura of

Baruch Spinoza

in Alan of

Lille. Alan of

Lille neither

deifies Nature,

nor naturalizes

God. There is no

conflation of

God and Nature.

Nature here

ends her

introduction,

and it does the

poet well, as he

spews forth,

vomiting as it

were, the "dregs

of phantasy"

that had

captured his

mind. These are

words we would

want modern man

to say: Omnes

phantasiae

reliquias quasi

nauseans,

stomachus mentis

evomuit. The

stomach of

modern man's

mind should

vomit all the

leavings, the

residue, the

remains of

fantasy that

give him la

nausée de Sartre,

the Sartrean

nausea. Nature

is just the

thing that can

take him away

from

existentialism

to essentialism,

from autonomy to

physionomy and

ultimately to

theonomy. Man

ought to do what

the poet does

once he upchucks

falsehood:

I fell down

at Nature's

feet and

marked them

with the

imprint of

many a kiss

to take the

place of

formal

greeting.

Then

straightening

up and

standing

erect, with

humbly bowed

head, I

poured out

for her, as

for a divine

majesty, a

verbal

libation of

good wishes.

Salutationis

vice, pedes

osculorum

multiplici

impressione

signavi. Tum

me explicans

erigendo,

cum

reverenti

capitis

humiliatione

velut

majestati

divinae, ei

voce viva

salutis

obtuli

libamentum.

In such position

of humility and

submission, and

his mind being

clarified of the

poisons that had

made it sick,

the poet asks

his question of

Nature: why is

it that she has

paid him such a

extraordinary

visit?

(continued)

RELEASED FROM HIS INTELLECTUAL

DISEASE by his acceding to

Nature's guidance, the poet in

Alan de Lille's De

Planctu Naturae sings

a paean of praise to Nature in

Sapphic meter.

|

O child of God, mother of

creation,

Bond of the

universe and its stable

link, Bright gem for those

on earth, mirror for

mortals,

Light-bearer for

the world.

Peace, love, virtue,

guide, power, order, law,

end, way, leader, source,

Life, light, splendour,

beauty, form,

Rule of the

world:

You, who by your reins

guide the universe, Unite

all things in a stable and

harmonious bond and

Wed

heaven to earth in a union

of peace;

Who, working on

the pure ideas of Nous,

mould the species of all

created things,

Clothing

matter with form and

fashioning a mantle of form

with your thumb:

You whom

heaven cherishes, air

serves, Whom earth worships,

water reveres;

To whom,

as mistress of the universe,

Each and every thing pays

tribute:

You, who bind

together day and night in

their alternations,

Give

to day the candle of the

sun,

Put night's clouds

to bed by the moon's bright,

reflected light:

You, who

gild the sky with varying

stars Illuming our ether's

throne, fill heaven with The

gems of constellations and a

varied

Complement of

soldiers: You, who in a

protean role, keep changing

heaven's face with new

shapes,

Bestow a throng

of birds on our expanse of

air and control them by your

law:

You, at whose nod

the world grows young again,

The grove is frilled with

foliage-curls,

The land,

clad in its garment of

flowers, shows its pride:

You, who lay to rest and

raise on high the

threatening sea as you cut

short the course of the

raging deep so that the

ocean's waves may not entomb

the sun's face.

|

O Dei proles, genitrixque

rerum,

Vinculum mundi,

stabilisque nexus,

Gemma

terrenis, speculum caducis,

Lucifer orbis.

Pax, amor, virtus, regimen,

potestas,

Ordo, lex,

finis, via, dux, origo,

Vita, lux, splendor,

species, figura

Regula

mundi.

Quae tuis mundum moderas

habenis,

Cuncta concordi

stabilita nodo

Nectis et

pacis glutino maritas

coelica terris.

Quae Noys

plures recolens ideas

Singulas rerum species

monetans,

Res togas

formis, chlamidemque formae

Pollice formas.

Cui favet

coelum, famulatur aer,

Quam colit Tellus, veneratur

unda,

Cui velut mundi

dominae, tributum

Singula

solvunt.

Quae diem nocti

vicibus catenans

Cereum

solis tribuis diei,

Lucido lunae speculo

soporans

Nubila noctis.

Quae polum stellis variis

inauras,

Aetheris nostri

solium serenans

Siderum

gemmis, varioque coelum

Milite complens.

Quae

novis coeli faciem figuris

Protheans mutas aridumque

vulgus

Aeris nostri

regione donans,

Legeque

stringis.

Cujus ad nutum

juvenescit orbis,

Silva

crispatur folii capillo,

Et tua florum tunicata

veste,

Terra superbit.

Quae minas ponti sepelis, et

auges,

Syncopans cursum

pelagi furori

Ne soli

tractum tumulare possit

Aequoris aestus. |

After this hymn of praise, the

poet asks Nature a series of

questions, questions that Nature

will later answer. Nature had

her plaint, now the poet as a

representative of mankind, has

his own pleading. At this stage,

he asks her a series of

questions.

|

Do you in answer to my plea

disclose

The reason for

your journey.

Why do you,

a stranger from heaven,

Make your way to earth?

Why do you offer the fit

of your divinity to our

lands?

Why is your face bedewed

with a flood of tears?

What do the tears on

your face portend?

|

Tu viae causam resera

petenti,

Cur petis terras, peregrina

coelis?

Cur tuae nostris

deitatis offers

Munera terris?

Ora cur fletus

pluvia rigantur?

Quid tui vultus

lacrymae prophetant?

|

We do not often see the results

of our moral corruption to the

order of Nature, or perhaps

better said, we ignore them. And

Nature gently chastises our poet

for not knowing what he drawn

her to the "common brothels of

earth" (vulgaria

terrenorum lupanaria).

The moral corruption,

specifically the homosexual

activity witnessed by the poet

with which the poem began, is an

intrinsic disorder from the

order of Nature, one that

affects its workings every bit

as much as if the earth deviated

from its rotation. It bespeaks

of carelessness on the part of

the caretakers of the world, an

act of injustice against

justice. It ought to be no

surprise to see Nature there

wishing order to be be imposed,

her law to be followed, her rule

conformed to.

All things, Nature explains, are

under her rule. All but man is

under a rule of strict

compliance. Man alone has

freedom and must freely or

voluntarily submit to Nature's

rule, the deviation from which

he intrinsically finds noxious

or injurious to him. Man is

Nature's anomaly. He alone can

deviate from Nature, even though

it is noxious or injurious to

him.

|

As all things by the law

of their origin are held

subject to my laws and

are bound to pay me the

tribute rightly imposed,

practically all obey my

edicts as a general

rule, by bringing

forward the rightful

tribute in the manner

appointed by law.

However from this

universal law man alone

exempts himself by a

nonconformist

withdrawal. . . .

Other creatures that I

have equipped with

lesser gifts from my

bounty hold themselves

bound in voluntary

subjection to the

ordinances of my decrees

according to the rank of

each's activity. Man,

however, who has all but

drained the entire

treasury of my riches,

tries to denature the

natural things of nature

and arms a lawless and

solecistic Venus to

fight against me. She

how practically

everything, obeying the

edict I have

promulgated, completely

discharges the duties

imposed by my law as the raison

d'etre of

its native condition

demands.

|

Cum omnia lege suae

originis meis

legibus teneantur

obnoxia, mihique

debeant jus statuti

vectigalis

persolvere, fere

omnia tributarii

juris exhibitione

legitima, meis

edictis regulariter

obsequuntur; sed ab

hujus universitatis

regula, solus homo

anomala exceptione

excluditur . . . .

Caetera quibus meae

gratiae humiliora

munera commodavi,

per suarum

professionum

conditionem

subjectione

voluntaria meorum

decretorum

sanctionibus

alligantur; homo

vero qui fere totum

divitiarum mearum

exhausit aerarium,

naturae naturalia

denaturare

pertentans, in me

scelestae Veneris

armat injuriam.

Attende, quomodo

fere quaelibet juxta

mei promulgationem

edicti, prout ratio

nativae conditionis

expostulat, mei

juris statuta

persolvant.

|

Man is homo

. . . naturae naturalia

denaturare pertentans,

a creature that can denature

that which naturally

pertains to his nature. It

is the concomitant to his

voluntary submission, the

freedom of his powers, which

are to be used by him in a

manner compliant to Nature.

Man, nevertheless, abuses

these powers. So it is that:

"He, stripping himself of

the robe of chastity,

exposes himself in

unchastity for a

professional male prostitute

and dares to stir up the

tumult of legal strife

against the dignity of his

queen, and, moreover, to fan

the flame of civil war's

rage against his mother."

The planets, the sun and

moon, the stars, the air and

its birds, the waters and

the fish they contain, the

earth and its beasts, all

follow Nature, and so all

these cooperate in a

harmonious pattern and are

fruitful. None abuse

sexuality in the way that

man does.

|

Man alone turns with

scorn from the

modulated strains of

my cithern and runs

deranged to the

notes of mad

Orpheus' lyre. For

the human race,

fallen from its high

estate, adopts a

highly irregular

(grammatical) change

when it inverts the

rules of Venus by

introducing

barbarisms in its

arrangement of

genders. Thus many,

his sex changed by a

ruleless Venus, in

defiance of due

order, by his

arrangement changes

what is a

straightforward

attribute of his.

Abandoning in his

deviation the true

script of Venus, he

is proved to be a

sophistic

pseudographer.

Shunning even a

resemblance

traceable to the art

of Dione's daughter,

he falls into the

defect of inverted

order. While in a

construction of this

kind he causes my

destruction, in his

combination he

devises a division

in me.

|

Solus homo meae

moderationis

citharam

aspernatur; et

sub delirantis

Orphei lyra

delirat: humanum

namque genus a

sua generositate

degenerans, in

conjunctione

generum

barbarizans,

venereas regulas

immutando, nimis

irregulari

utitur

metaplasmo:

sicque homo a

venere

tiresiatus

anomala,

directam

praedicationem

in

contrapositionem

inordinate

convertit. A

Veneris igitur

orthographia

homo deviando

recedens,

sophista

falsigraphus

invenitur.

Consequenter

etiam Dioneae

artis analogiam

devitans, in

anastrophem

vitiosam

degenerat.

|

Man alone can corrupt

his natural language, and so

fall from moralorthographus or

orthography to moral falsigraphus to

heterography or falsigraphy.

He alone is capable into

falling into venereal

anomaly, and so barbarizes

and corrupts the sexual

grammar which ought to

govern the use of his sexual

faculties. Man's accession

to Venus's lawless ways

seems almost endemic

throughout his history. The

abuse of the grammar of the

sexual faculties is seen in

historical or mythical

figures: Helen defiles her

marriage bed in her

adulterous dalliance with

Paris; Pasiphae, the wife of

Minos, King of Crete, lusted

after Poseidon's bull, and

even had Daedalus build a

shell in the form of a

heifer so that she would

trick the bull into having

relations with her, falling

into a gross bestiality and

resulting in the Minotaur;

Myrrha unnaturally

incestuously desired her own

father, Cinyras; similarly

Medea killed the offspring

of her own body in spiteful

vengeance to her husband

Jason who had abandoned her;

Narcissus destroyed himself

by his self-love. Of the men

that fall into the hands of

lawless Venus, the variety

is legion:

|

Of those men who

subscribe to Venus'

procedures in grammar,

some closely embrace

those of masculine

gender only, others,

those of feminine

gender. Some, indeed, as

though belonging to the

heteroclite class

[showing more than one

declension], show

variations in deviation

by reclining with those

of female gender in

Winter and those of

masculine gender in

Summer. There are some,

who in the disputations

in Venus' school of

logic, in their

conclusions reach a law

of interchangeability of

subject and predicate.

There are those who take

the part of the subject

and cannot function as

predicate. There are

some who function as

predicates only but have

no desire to have the

subject term duly submit

to them. Others,

disdaining to enter

Venus' hall, practice a

deplorable game in the

vestibule of her house.

|

Eorum siquidem

hominum qui Veneris

profitentur

grammaticam, alii

solummodo

masculinum, alii

feminum, alii

commune, sive

promiscuum genus

familiariter

amplexantur: quidam

vero quasi

heterocliti genere,

per hiemem in

feminino, per

aestatem in

masculino genere

irregulariter

declinantur. Sunt

qui in Veneris

logica disputantes,

in conclusionibus

suis, subjectionis,

praedicationisque

legem relatione

mutua sortiuntur.

Sunt, qui vicem

gerentes supposito,

praedicari non

norunt. Sunt, qui

solummodo

praedicantes,

subjecti

subjectionem

legitimam non

attendunt. Alii

autem Diones regiam

ingredi dedignantes,

sub ejusdem

vestibulo ludum

lacrymabilem

comitantur.

|

It is in view of the current

abuses of the sexual faculties

among men that Nature has

traveled down from heaven to pay

a visit to the poet, and which

forms the central part of her

complaint.

For this

reason, then, did I leave

the secreted abode of the

kingdom in the heavens above

and come down to this

transitory and sinking world

so that I might lodge with

you, as my intimate and

confidant, my plaintive

lament for the accursed

excesses of man, and might

decide, in consultation with

you, what kind of penalty

should answer such an array

of crimes so that

conformable punishment,

meting out like for like,

might repay in kind the

biting pain inflicted by

tghe above-mentioned

misdeeds.

Ideo enim a

supernis coelestis regiae

secretariis egrediens, ad

hujus caducae terrenitatis

occasum deveni, ut de

exsecrabilibus hominum

excessibus, tecum quasi cum

familiari et secretario meo,

querimoniale lamentum

exponerem, tecumque

decernerem, tali criminum

oppositioni, qualis poenae

debeat dari responsio: ut

praedictorum facinorum

morsibus coaequata punitio,

poenae talionem remordeat.

MEN WHO DISREGARD THE

GRAMMAR OR THE LOGIC OF

SEXUALITY, that is, the ratio

ordinis inherent

in Nature's plan,

deserve to be punished.

This is the reason that

Nature left her heavenly

abode and appeared to

the poet in the

"transitory and sinking

world." The complaint

that Nature has filed

against mankind seeks

for its relief a

penalty, one

commensurate or

proportionate to the

array of mankind's

sexual crimes.

But the poet has

another question for the

"mediatrix in all

things," the rerum

omnium mediatrix that

Nature is under God's

order. He harbors some

doubt, and wishes it

addressed. Why does

Nature take mankind to

task, and not address

the sexual aberration

among the Greek gods?

What about Jupiter and

his love for his young

Phrygian cup bearer

Ganymede? What about

Apollo, who loved the

youths Hyacinthus and

and Cyparissus? And

Bacchus, and his

proclivities to young

transvestites?

Nature detects the

psychological

defense mechanism of

rationalization

behind her

interlocutor's

reference to the

poets, and it draws

the same response as

one might see in

Plato, who banished

the poets from his

ideal Republic. It

is the excuse of

Byblis, who sought

thereby to justify

her lawless love for

her brother, Caunus,

which, unfulfilled,

caused her in her

pining desire to

turn into a spring.

"If the gods do

these things," goes

the rationalization,

"why not me?"

(Moderns have

transmuted the

excuse from immortal

gods to mortal

celebrities, but the

thought process is

the same.) Poets,

like television

programs or modern

newscasters, are not

to be trusted, and

no credence is to be

given to their

"shadowy figments,"

their figmentis

umbratilibus.

The poets are, in

fact, deceitful:

Do you not know

how the poets

present

falsehood, naked

and without the

protection of

covering, to

their audience

so that, by a

certain

sweetness of

honeyed

pleasure, they

may, so to

speak,

intoxicate the

bewitched ears

of the hearers?

Or, how they

cover falsehood

with a kind of

imitation of

probability so

that, by a

presentation of

precedents, they

may seal the

minds of men

with a stamp

from the anvil

of shameful

tolerance?

An ignoras,

quomodo poetae

sine omni

palliationis

remedio,

auditoribus

nudam falsitatem

prostituunt, ut

quadam mellita

dulcedine velut

incantatas

audientium aures

inebrient?

Quomodo ipsam

falsitatem

quadam

probabilitatis

hypocrisi

palliant, ut per

exemplorum

imagines,

hominum animos

moriginationis

incude

sigillent?

(One can suppose

that Hollywood and

modern television

have taken the

socially corrosive

role of the ancient

Pagan poets.

Modernly, these

fulfill the same

deconstructive role

the poets of old

that Nature (like

Plato) execrates.

They artificially

palliate the

conscience of its

sin with soma not

sacrament, they

justify it, they

give it the

appearance of good,

they avoid any

mention of its

social or moral

consequences. They

present sin as

viable choice, as a

valid preference, or

legitimate and

individual

self-expression.

They bewitch many an

ignorant to step

into the life of

moral fog that

smells, if one

retained one's sense

of smell, like the

burnings of human

refuse at Gehenna.

Using Tertullian's

words, these are the

new Pagan pompa

diaboli et

daemoniorum,

the pomps of the

devil and his

demons. But to get

back to Alan of

Lille . . .)

Nature observes

that the poets have

no place in

contemporary (then

medieval) life,

since shed are the

philosophies and

heresies that

falsely touted

pleasure and lies,

and thereby hid from

their followers the

one true God. "Over

these statements" of

the past, "I draw

the cloud of silence

. . . .":

For since the dreams

of Epicurus are now

put to sleep, the

insanity of [the

heresiarch]

Manichaeus healed,

the subtleties of

Aristotle made

clear, the lies of

Arrhius [the heretic

Arius] belief, the

reason proves the

unique unity of God,

the universe

proclaims it, faith

believes it,

Scripture bears

witness to it. No

stain forces its way

to Him, no baneful

vice makes an

assault on Him, no

impulse of

temptation is

associated with Him.

He is the bright

light that never

fades (splendor

nunquam deficiens),

the life that never

tires or dies (vita

indefessa, non

moriens), the

fountain that ever

flows (fons

semper scaturiens),

the seed-plot

supplying the seed

of life (seminale

vitae seminarium),

the principle

principle of wisdom

(apiens principale

principium), the

original origin of

good (initiale

bonitatis initium).

The poet has other

questions, and Nature

welcomes them. Harking

back to her tunic, he

asks why some parts of

her tunic, which one

would expect to

"approximate the

interweave of a

marriage," are rent,

precisely where man's

picture ought to be. (For

a description of the

robe and its torn

fabric, see Part 2 of

this series.)

The tears in

Nature's tunic represent

the assault on Nature

herself by man. Their

vices against Nature,

which are nothing other

than the "chaos of

ultimate dissension," maximum

chaos dissensionis,

is a form of violence.

They commit violence

against Nature herself,

and she who should be

honored is thus stripped

and treated as a harlot.

"This is the hidden

meaning symbolized by

this rent--that the

vesture of my modesty

suffers the insults of

being torn off by

injuries and insults

from man alone."

The poet then is

interested in knowing

"what unreasonable

reason, what indiscreet

discretion, what

indirect direction

forced man's little

spark of reason to

become so inactive that,

intoxicated by a deadly

draught of sensuality,

he not only became an

apostate from your laws,

but even made unlawful

assaults on them." What

has caused man to act so

against order?

To answer the

question, Nature

requires the poet to

inflame his reason, to

focus his attention, and

to understand that

Nature intends to use

words that are not

vulgar or uncouth.

Nature then describes,

in terms of the marital

relationship, the

relationship between God

and his Ideas and the

creation of the Universe ex

nihilo, from

out of nothing

pre-existing. Out of

nothing, in accordance

with His eternal ideas,

God brought forth

numerous species, and he

separated them from, or

tempered them of,

chaotic strife, "by

agreement from [i.e.,

congruency with] law and

order," legitimi

ordinis congruentia

temperavit.

He imposed laws on

them.

Leges indidit.

He bound them by

sanctions.

Sanctionibus

alligavit.

By a tension of

opposites he created

harmony with a "fine

chain of an invisible

connection," subtilibus

. . . invisibilis

juncturae catenis,

God made it so that

there would be in a

peaceable union

"plurality [to strive

back] to unity,

diversity to identity,

discord to concord." All

things were so related

as to be veritably wed

to one another as if in

a relationship of lawful

marriage.

When

the artisan of the

universe had clothed

all things in the

outward aspect

befitting their

natures and had wed

them to one another

in the relationship

of lawful marriage,

it was His will that

by a mutually

related circle of

birth and death

transitory things

should be given

stability by

instability,

endlessness by

endings, eternity by

temporariness and

that the series of

things should ever

be knit be

successive renewals

of birth. He decreed

that by the lawful

path of derivation

by propagation, like

things, sealed with

the stamp of

manifest

resemblance, should

be produced from

like.

Sed

postquam universalis

artifex universa

suarum vultibus

naturarum

investivit, omniaque

sibi invicem

legitimis

proportionum

connubiis maritavit,

volens ut nascendi,

occidendique mutuae

relationis circuitu

per instabilitatem

stabilitas, per

finem infinitas, per

temporabilitatem

aeternitas rebus

occiduis donaretur,

rerumque series

seriata

reciprocatione

nascendi jugiter

texeretur, statuit,

ut expressae

conformationis

monetata sigillo,

sub derivandae

propagationis calle

legitimo, ex

similibus similia

educerentur

God, the Creator of all

things, appointed Nature

his substitute (sui

vicariam), the

manager of God's mint in

charge of stamping and

molding each thing in

its image, so that "the

face of the copy should

spring from the

countenance of the

exemplar and not be

defrauded of any of its

natural gifts," operando

quasi varia rerum

sigillans cognata ad

exemplaris rei imaginem

exempli exemplans

effigiem, ex conformibus

conformando conformia,

singularum rerum reddidi

vultus sigillatos.

Yet this God, which

is the Creator, is not

the distant God of the

Deist, but the God of

near Providence.

Nature's work was

constantly monitored,

"guided by the finger of

the superintendent on

high," supremi

dispositoris digito

regeretur. Nature

was therefore God's

agent, and Nature took

another as sub-agent, a subvicaria,

a "sub-delegated

artisan," subministratori

artificis. This

was none other than

Venus who, with the aid

of Hymenaeus her spouse,

and Desire [Cupid], her

son, would help in the

reproduction of the

animal life on earth,

"fitting her artisan's

hammer to the anvil

according to rule,"

which would thereby

"maintain an unbroken

linkage in the chain of

the human race lest it

be severed by the hands

of the Fates and suffer

damage by being broken

apart." Nature was

thereby to spend time in

the ethereal regions in

the calm of her palace.

Or so was the plan.

The poet now

chuckles (even laughs

like the superannuated

Sarah did at overhearing

that she, at her age,

would bear a child to

Abraham) at the mention

of Desire, for he

recognizes its universal

power and dominion over

all mankind, truly a

non-respecter of

persons, and he perhaps

too emboldened wishes to

have a better

description of this

Desire. The poet

receives a stinging

rebuke from Nature:

|

I believe that

you are a

soldier drawing

pay in the army

of Desire and

are associated

with him by some

kind of

brotherhood

arising from

deep and close

friendship. For

you are eagerly

trying to trace

out his

inextricably

labyrinth when

you should

rather be

directing your

attention of

mind more

closely to the

account enriched

by the wealth of

my ideas.

However, since I

sympathise with

your human

frailty, I

consider myself

bound to

eliminate, as

far as my modest

power allow, the

darkness of your

ignorance before

the course of my

narrative goes

on to what

follows next in

order.

|

Tunc illa, cum

temperato

capitis motu,

verbisque

increpationem

spondentibus,

ait: Credo te in

Cupidinis

castris

stipendiarie

militantem, et

quadam

interfamiliaritatis

germanitate

eidem esse

connexum:

inextricabilem

etenim ejusdem

labyrinthum

affectanter

investigare

conaris, cum

potius meae

narrationi

sententiarum

locupletatae

divitiis, mentis

attentionem

attentius

adaptare

deberes. Sed

tamen antequam

ad sequentia

meae orationis

evadat excursus,

quia tuae

humanitatis

imbecillitati

compatior,

ignorantiae tuae

tenebras, pro

meae

possibilitatis

volo modestia

exstirpare.

|

And so it is that

Nature, bound by a vow

and promise to answer

the poet's questions,

with describe the

indescribable, define

the undefinable,

demonstrate the

indemonstrable,

extricate the

inextricable, delimit

that which is without

limit, explain something

that is, by nature,

inexplicable, try to

teach doctrine that is

unknowable. In short,

with reason to elaborate

on the unreasonable:

Desire, the concupiscent

cupidity of Cupid, child

of the unmanageable

Venus.

NATURE ANSWERS THE

POET'S QUERY

regarding the nature

of Desire with a

poem in elegiac

meter. Desire (cupido)

or cupidity is

equated with love (amornot caritas),

and its largely

irrational character

is emphasized by the

paradoxes through

which it operates

and in which it

seems to relish.

Nature ends her

description of

Desire on some

practical advice on

how to avoid Venus

and her child,

Desire.

|

Love is

peace joined

to hatred,

Loyalty to

treachery,

Hope to fear

and madness

blended with

reason.

It is

sweet

shipwreck,

light

burden,

pleasing

Charybdis,

Sound

debility,

insatiate

hunger,

hungry

satiety,

thirst when

filled with

water,deceptive

pleasure,

happy

sadness,

joy full of

sorrow,

delightful

misfortune,

unfortunate

delight,

sweetness

bitter to

its own

taste.

Its

odour is

savoury,

Its savour

is insipid.

It is a

pleasing

storm,

a

lightsome

night,

a

lightless

day,

a

living

death,

a

dying life,

a pleasant

misery,

pardonable

sin,

sinful

pardon,

sportive

punishment,

pious

misdeed,

nay, sweet

crime,

changeable

pastime,

unchangeable

mockery,

weak

strength,

stationary

movable,

mover of the

stationary,

irrational

reason,

foolish

wisdom,

gloomy

success,

tearful

laughter,

tiring rest,

pleasant

hell,

gloomy

paradise,

delightful

prison,

spring-like

Winter,

wintry

Spring,

misfortune.

It is a

hideous worm

of the mind

which the

one in royal

purple feels

and which

does not

pass by the

simple cloak

of the

beggar.

Does not

Desire,

performing

many

miracles, to

use

antiphrasis,

change the

shapes of

all mankind?

Though monk

and

adulterer

are opposite

terms, he

forces both

of these to

exist

together in

the same

subject.

When his

fury rages,

Scylla lays

aside her

fury and

Nero begins

to be the

good Aeneas,

Paris sword

flashes,

Tydeus grows

soft with

love, Nestor

becomes a

youth,

Milcerta

becomes an

old man.

Thersites

begs Paris

for his

beauty and

Davus begs

the beauty

of Adonis,

who is

totally

transfromed

into Davus.

The wealthy

Croesus is

in need;

Codrus, the

beggar,

abounds in

wealth.

Bavius

produces

poems,

Maro's muse

grows dull;

Enius makes

speeches and

Marcus is

silent.

Ulysses

becomes

foolish,

Ajax in his

madness

grows wise.

The one who

formerly won

the victory

by dealing

with the

tricks of

Antaeus,

though he

subdues all

other

monsters, is

overcome by

this one.

If this

madness

sickens a

woman's

mind, she

rushes into

any and

every crime

and on her

own

initiative,

too.

Anticipating

the hand of

fate, a

daughter

treacherously

slays a

father, a

sister slays

a brother,

or a wife, a

husband.

Thus by

aphairesis

she wrongly

shortens her

husband's

body when

with

stealthy

sword she

cuts off his

head. The

mother

herself is

forced to

forget the

name of

mother and,

while she is

giving

birth, is

laying

snares for

her

offspring. A

son is

astonished

to encounter

a stepmother

as his

mother and

to find

treachery

where there

should be

loyalty,

plots where

there should

be

affection.

Thus in

Medea two

names battle

on equal

terms when

she desires

to be mother

and

stepmother

at the same

time. When

Byblis

became too

attached to

Caunus, she

could not be

a sister or

conduct

herself as

one. In the

same way,

too, Myrrha

submitting

herself too

far to her

father

became a

parent by

her sire and

a mother by

her father.

But why