Life and work

François Vatable (appointed in 1530 as royal lecturer of Hebrew in Paris) is mainly, if not exclusively, remembered for his collaboration with Robert Estienne in the production of the famous 1545 Latin Bible in which the old Bible translation (Vulgate) and a new one directly translated from the Hebrew are printed side-by-side. The ensemble is accompanied by annotations which – according to Estienne in his preface – were based on, among others, student notes (reportationes) taken at the public lectures (praelectiones) of François Vatable.1 These notes (glossa, annotationes) therefore became known as the ‘Vatable notes’ (notes de Vatable) and the Bible edition itself as the ‘Vatable Bible’ (Bible de Vatable). The content of some of these notes led to an escalation of the already existing tensions between the printer, Robert Estienne, and the Paris theologians. When it came to open polemics and censure, the supposed author, François Vatable, had already died (16 March 1547).2

An intriguing aspect of these notes is that almost everything about them is uncertain, even their proper identification poses difficulties: ‘which notes are we talking about?’: the notes in the 1545 Paris Bible or the notes in the 1557 Geneva Bible, both printed by Robert Estienne and both often simply referred to as Vatable’s.3 Nevertheless these notes are not identical: in 1557 they are more extensive (sometimes more technical, sometimes more preachy). Both sets of notes have originated a text-tradition of their own. The 1557 notes were often reprinted in protestant Bible editions, and – in the 17th century – included in Critici Sacri (an immensely popular multi-volume compendium of scholarly biblical knowledge from the past). The 1545 Bible became the object of an inquisitorial tug of war in Spain. It was censored, resulting in a 22 column list of corrections to be implemented. As such it was published by André de Portonariis (1555) and banned again, then reedited by three theologians of Salamanca (a.o. Luys de León) and finally printed by André’s brother, Gaspard de Portonariis, authorized in 1573, published in 1584. On the title page the glosses are advertised as being Vatable’s.4 In Bible editions and secondary literature based on both text traditions the glosses are generally introduced with phrases like ‘Vatablus vertit’ or ‘ut interpretatur Vatablus’,5 surprisingly concerning both Old and New Testament notes, although not even Estienne ever claimed that Vatable, professor of Hebrew, was also the editor of the New Testament notes. The custom indiscriminatingly to refer to either the 1545, 1567 and 1584 Bible (and its descendents) as the ‘Vatable Bible’ and to all notes therein as the ‘Vatable notes’ persists until today.

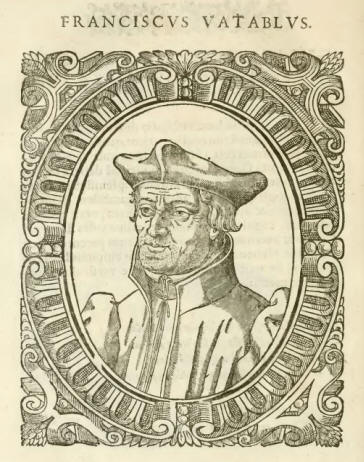

The aim of this article is to shed some light on this question, but only indirectly. In my opinion too much energy has been spent on a subquestion: whether or not these notes are Vatable’s, and even to a sub-subquestion: whether or not they contain ‘heresy’. This debate dates back to the 16th century (beginning with the censorship of the Paris theologians in 1547/8) and is seriously contaminated by the propaganda from both sides. The main victim in this debate is not Robert Estienne and his Bible (he has defended himself vigorously and his Bible editions were a success) but the person and work of François Vatable who is so much more than a ‘name’ associated with ‘biblical annotations’ in one particular Bible edition. He was one of the most eminent scholars of the early sixteenth century and deserves to be met without a direct reference to the Estienne Bible and the notes that carry his name. Even more: the notes should not serve to establish his theological view (heterodox/orthodox), but should be used – if possible – to shed light on his Hebrew scholarship. Therefore I propose to – temporarily – put the question about the notes to one side and only address it in due course, i.e., when the story of Vatable’s life and work can benefit from their treatment.

Early life and studies.

François Vatable was born in Gamaches (Picardy) as François Wattebled,6 year/date of birth unknown, but probably in the last decade of the 15th Century. He was a son of Jean Wattebled and Péronne Le Fèvre. In his will two sisters (Jeanne and Antoinette) and a number of nieces are mentioned, no brothers.7

| Gamaches, Eglise de Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul (most ancient parts date from the 13th C) |

An old and persistent tradition claims that he was a priest in a little town in the Valois, Brumetz, before he enrolled as student at the Faculty of Arts in Paris. This can’t be true because – as we will see below – he was still very young when he arrived in Paris. What is true, however, is that in his later days the curacy of Brumetz was used to provide his income as royal lecturer.8 The first certified fact about Vatable’s life is an entry in the 1511 Registers of the University of Paris which mentions that he applied for a benefice in Amiens. In the application he is referred to as Master of Arts.9 To get a Master’s degree five years of preparatory studies were required. This implies that the young François must have arrived in Paris around 1506.10 From 1511 onwards his name appears in books and other documents, which provides us with the possibility to construct a provisory and tentative chronology about his life as a lector (licentia docendi) at the Faculty of Arts and his early career. An overview:

-

In 1511 Girard Roussel11 mentions Vatable in a preface to a publication of works on Aristotelian logic (Logices adminicula). He is introduced as a collaborator and friend who is still an ‘adulescens’. In the same book a second preface, signed ‘Franciscus Vatablus Gamachianus’, is printed on f° 26v.12

The

book in question was meant for students at the Paris Faculty of

Arts, where philosophy was an important part of the curriculum: a

textbook.

The

book in question was meant for students at the Paris Faculty of

Arts, where philosophy was an important part of the curriculum: a

textbook. -

In 1512 we find Vatable among the students of Girolamo Aleandro, the Italian scholar, who taught the French to read and write Greek and was the rector of the University of Paris for a three-month term in 1512 (in his later years he made a career as papal nuncio confronting Luther in Germany). On his behalf, François Vatable completed the edition of the Greek grammar of Chrysoloras, which he was editing for publication when he fell ill. This edition is the first in which the revolutionary new Greek characters, typecast by Gilles de Gourmont, were used.13

Not bad for a young man: Vatable was a rising star in academic circles – department philosophy – in Paris in the early 1510s. The production of new Latin translations of Greek philosophical treatises was typical for the humanist movement in those days. Scholarly, pedagogically and spiritually the Faculty of Arts was strongly influenced by Lefèvre d’Etaples, one of its leading professors. Apparently: languages were Vatable’s forte: Greek for the moment, not Hebrew, although Aleandro was well versed in that language too. Graduated in or before 1511, he must still have been quite young, since a reference to his youth is always present when he is referred to. Roussel calls him an ‘adulescens’ (the same term he used to address the students in his preface), and two years later, 1513, Charles Brachet, one of Aleandro’s most brilliant students, refers to his friend Vatable also as a ‘iuvenis’ (preface to his translation from Greek into Latin of three Dialogues of Lucianus14). Calling someone a ‘iuvenis’ in 1513, implies that by then Vatable could not be much older than 18. We can not but conclude that François must have been a precocious boy. Calculating backwards we propose – tentatively – the following dates: born ca. 1495 in Gamaches (Picardy), arrival in Paris ca. 1506 (still a boy), graduating as M.A. in or prior to 1511, quite young but not impossible.15 In the meantime his talent for languages and philosophy was discovered and his academic career is launched. In 1513 he would be still young enough to be called a ‘iuvenis’ (18 years of age) by someone who himself was certainly not much older, but also old enough to supervise the edition of books on behalf of renowned scholars like Roussel and Aleandro. The way he addresses the supposed readers in his preface is telling: he clearly is not one of them anymore.16 The image that appears is that of a young, dynamic post-graduate member of the Faculty of Arts in Paris, active at the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine, first as a student and now teaching there himself.17

This image is confirmed by the next step in his career. After having perfected his knowledge of the Greek tongue under the tutelage of Aleandro, he moves to Avignon to study Hebrew.18 The time when one could only become a Hebraist as an autodidact was past. Published grammars and dictionaries were not yet flooding the market and the tri-lingual colleges had still to be founded. There were incidental almost personal inititatives to promote the study of Hebrew. In Paris François Tissard had lectured and had published a book containing the basics of Hebrew writing in 1508, and in 1514 the already mentioned Aleandro published a Greek and Hebrew alphabet, but this apparently did not result in systematic teaching in this language.19 In 1518-1522 Antonio Giustiniani, a famous scholar, both Hebraist and Arabist, gave lectures on Hebrew in Paris at the King’s request.20 Vatable however did not wait until all these initiatives had been finalized, but left Paris for Avignon to enhance his mastery of the Hebrew language in order to make the ‘litterae Hebraeae’ as useful for Christians as the Latin and Greek already were. He probably chose Avignon, because it was almost the only place in France where Jewish communities were still allowed – be it with strict regulations – to exist and participate in public life.21 When he returns from Avignon, now well versed in Latin, Greek ànd Hebrew, he once again is found in the company of Lefèvre d’Etaples, who was still staying in the prestigious Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, a guest of the abbot there: Guillaume Briçonnet. This time, and on the explicit request of his ‘Master and Maecenas’ Lefèvre d’Etaples,22 Vatable embarks on the revision and translation (from the Greek) of a number of important philosophical treatises of Aristotle, thus taking up the thread as scholarly editor. He revises the old medieval Latin translations, edits available up-to-date translations (Argyropoulos), and if no modern translation available, he provides one based on available Greek manuscripts and the famous Aldus-edition. This voluminous book (336 folios) contains the old and the new translation side by side (the old though in a larger type), with summarising introductions and marginal notes. It appeared in print in 1518 with Henri Estienne.23 The texts in question, Physica, De caelo, De anima, De generatione et corruptione, and the so called Parva naturalia are all works from Aristotle, “the Philosopher” as he was then called, dealing with the world we live in; inquiries in physics, human and animal nature, psychology, astronomy, and meteorology.

This book is one of the several substantial contributions of Lefèvre’s scholarly team which was devoted to restoring the works of Aristotle in their original splendour by republishing them from trustworthy sources in an up-to-date Latin translation. Next to Lefèvre himself (mainly paraphrasing commentaries) the main participants were Josse Clichtove, Charles de Bouvelles, and Girard Roussel. The effort was spread over three decades (1490-1522). A similar project concerning the patristic writings was effected parallel to it and in the second half of the 1510s (including publication of mystical writers, like Ruusbroec) a third project began to absorb their energy even more. This was the restoration of biblical texts, Lefèvre’s fivefold Psalter (Quincuplex Psalterium, 1509) being the forerunner. By means of fluent Latin translations (imported from Italy or self-made), commentaries, introductions and paraphrases, these scholars tried to recover and highlight the true value of these ancient works. They were working on a linguistic level – new translation into Latin following the rules of Latin syntax, grammar and idiom, rejecting the medieval way (almost verbally Latinising the Greek), because it was not acceptable anymore to the Latinists of the Renaissance and because it really obstructed the reading and understanding of the texts.24 Lefèvre d’Etaples, Girard Roussel and Josse Clichtove are often only mentioned in theological contexts (pro or contra Luther/Calvin, or something in between etc.). This not only wrongly neglects their multifaceted personalities, it also obscures the embedment of the theological issues in a much wider cultural debate. At the same time, it simply misrepresents the way these scholars were perceived and appreciated in their own days.25 Among these works, Vatable’s new translations of De generatione et corruptione, Meteorologica, and the parva naturalia, was the most successful and had the most long-lasting effects. Here, to illustrate what Vatable did – under the aegis of Lefèvre d’Etaples– a list of the works he edited and translated:

Early editions.

Aristotle: from his works on physical reality

a. Editor of a vetus et nova tralatio (Argyropoulos) of Aristotle (1518)

b. Editor of a vetus tralatio and provider of a nova tralatio from the Greek (1518)

His translations were reprinted many times and separate editions of them (in small booklets for students) were used to teach philosophy, not only in Paris, but also in Lyon, and soon also outside France.31 All his translations were included in Aristotle’s Opera omnia edition which appeared in Frankfurt in 1593.32 They were also part of the 1831 Aristoteles Latine.33 So, we conclude, before he became the Regius Professor of Hebrew, François Vatable was known as an able translator, editor and annotator of philosophical texts, specialist in the Greek tongue and expert in Aristotle’s natural philosophy.

German edition (Wittenberg, 1543 - NB: Luther's University)

Spanish

collection of Vatable's translations (Salamanca -

De Portonariis) 1555:

The Cercle de Meaux

Vatable’s 1518 edition and (partial) new translation of Aristotle’s parva naturalia and related texts was dedicated to Guillaume Briçonnet, Bishop of Meaux, who – in 1517 – had started a programme of reform in his diocese by visiting the parishes and organizing a synod. He also tried to improve the training of his clergy and monastic discipline. Another element of his reform was the implementation of a new style of preaching.34 To this end Briçonnet asked Lefèvre d’Etaples to come over and help him. With him came part of his circle of learned men, who were also clergymen, among them Martial Mazurier, Gérard Roussel, Michel d’Arande, Guillaume Farel, Pierre Caroli and François Vatable.35 Next to ecclesiastic reform (implementing already existing regulations based on the authority exercised by a resident and visiting bishop) the emphasis on the study of the Bible and the teaching of basic doctrine to everyone in the vernacular, was the core and kernel of Briçonnet’s initiative. Vatable, apparently still closely connected with Lefèvre d’Etaples, simply followed his mentor. In 1521 he is appointed priest in the diocese of Meaux, first in Saint-Germain-sous-Couilly, then in Quincy and finally he becomes a canon, a member of the chapter of the Cathedral of Saint-Estienne in Meaux. The bishop grants him a license to preach. Considering that this was an essential part of the reform program it can be assumed that he did it, although no mention of this activity is ever made (in contrast to other preachers). More obvious though, but often overlooked, is another kind of contribution.36 Parallel with the activity in the field (preaching, visiting), the printing press was put in overdrive, not so much to publish Artistotle,37 or patristic or mystic literature, but elementary biblical material, both the Bible text (first in parts, eventually resulting in the first entire Bible in French - 1530) and catechetical and homiletical material, practical, immediately useful, like Luther’s Postillen, to facilitate the reformation process. 38 What is more obvious than to assume that Vatable, not only a Graecist but now also a Hebraist, was involved in the translation activities, especially when the Old Testament was concerned? We can go a step further: Lefèvre was a Latinist and a Graecist, but in matters concerning Hebrew he only had a very basic knowledge and relied completely on others to provide him with information.39 The simple fact that in the scholarly edition of the Latin Psalter of 1524, extensive use is suddenly made of Jewish sources, carefully introduced and explained in the introduction, betrays the hand of a biblical scholar with intimate knowledge of the Hebrew text, the Jewish exegesis (Midrash) and rabbinical commentaries.40 In this edition the text of the Psalterium Gallicanum (‘Vulgate’) is printed with alternative readings in relevant places. The Hebraicum is not that of Jerome any longer (as it still was in the Quincuplex), but is replaced by a the translation of Felice de Prato (Felix Pratensis) straight from the Hebrew.41 Occasionally, a reading from a Chaldaicum (= Targum) is provided to help understanding. In Meaux there is only one person who had the required mastery of Hebrew to do this: François Vatable. His name is not mentioned, but this is not much of a surprise: the watching eye of the Theologians in Paris had already forced the circle of Lefèvre to hide their own and collective works behind anonymity. Gradually, the pressure from the conservative party in Paris became unsustainable, esp. since the King himself was in captivity in Madrid and his sister (the sponsor, protector and inspiration of the evangelicals42) had also left the country to negotiate the release of her brother. In 1525 the experiment collapsed. Briçonnet was summoned to appear before the Parlement, Lefèvre and Roussel fled to Strasbourg. Vatable seems to have left the group before the final blow was delivered. On 8 July 1524 he exchanged his canonry in Meaux cathedral for the rectory of Suresnes (diocese of Paris), retaining this benefice until his death.43 The other participants (mainly Arande, Roussel, Mazurier, Caroli) were never able to continue their life and work in France without being watched or attacked by the conservative party of Paris theologians. Without the protection of the Court the end of the ‘Meaux circle’ would have been even more fatal. Vatable’s participation in the experiment of Guillaume Briçonnet apparently did not harm his career. His ‘orthodoxy’ was not doubted and his name never appears in the proceedings of the Faculty of Theology that are edited for the years 1524—1550.44 So we can assume that he returned to Paris and resumed (or continued?) his activities in the bosom of the faculty of Arts. What is certain is that he fulfilled his promise, made in 1518, to procure a new edition of Lefèvre’s paraphrases on Artistotle’s Physics. It appeared in print in 1528, published by Simon de Colines.45

'le vieux

chapitre', episcopal Palace of Meaux (Briçonnet)

The royal lecturer

The facts about the remainder of his career are well known. In 1530 François I-er finally decided to provide the funds for lecturers in Greek (Jacques Toussain, Pierre Danès) and Hebrew (Agazio Guidacerio, François Vatable). A few month later a lecturer in Mathematics was also appointed (Oronce Finé) and in 1531 even a third Hebrew lecturer: a converted (or apostate) Jew, Paul Paradis.46 The Faculty of Theology looked at this project with Argus’ eyes, quite understandable since things associated with the Bible were no neutral issues anymore in 1530. Lectio implies reading, translating and explaining the meaning (sensus). And exactly that has always been the prerogative of the Faculty of Theology. Apparently the leading theologians wanted to set things straight right from the start by condemning two theses concerning the necessity of knowledge of the original tongues to be able to properly interpret the Bible. They made clear that the authority on interpretation of the Bible resided exclusively with the Faculty of Theology, with or without knowledge of the original tongues. So reading the Bible is alright, textual criticism of the Vulgate allowed (although close), but questioning the Truth based on the Vulgate was absolutely forbidden.47 That would be trespassing into their domain. Within these boundaries there seems to have been much less animosity in everyday college life between royal lecturers and ‘normal’ lecturers, than is (was?) often supposed. Tendentious statements, both contemporaneous and retrospective are not necessarily impartial descriptions of matters of fact. Of course there was animosity, distrust and competition, but that does not imply that this struggle should be sketched as a heroic battle of the enlightened elite (the good guys) against a retarded integrist party (bad guys). Life is too complex to be interpreted along such simple lines.48

More interesting to us is that Vatable’s name is mentioned in this context, but that the content of his lessons is never attacked. For everyone his personal integrity and good Christian Faith appeared to have been beyond doubt.49 For his contemporaries he is the scholar who had written textbooks for the courses in Philosophy used time and again in the official curriculum of the Faculty of Arts. As well as an expert in Aristotle’s physics, he is also an uncontested authority in matters concerning languages: Latin, Greek and Hebrew (both biblical and rabbinical Hebrew). He did not advertise his own thoughts nor publish his own lectures. He did not even publish a Hebrew grammar like many of his colleagues. Nevertheless it is incorrect to say that he did not leave a heritage outside his pupils (and their lecture notes, the reportationes) as is often said.50 This is an optical illusion.

Publications (with Estienne, biblical editions)

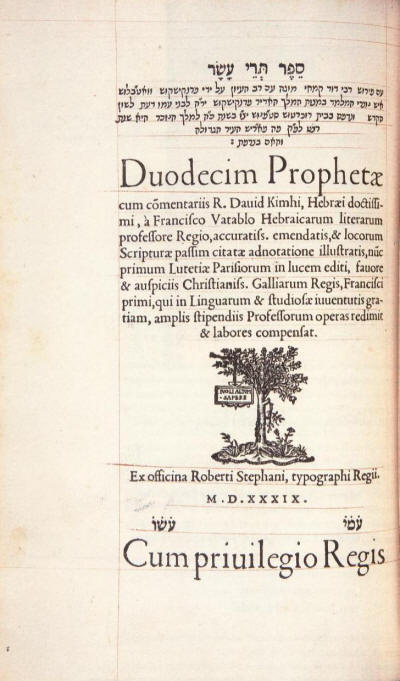

Vatable did publish, but – and here we find a continuum in his life – not thoughts or texts of his own, but texts of others. Just as he had done with Aristotle (editing, emending existing translations by referring to the original texts, and – if necessary – making new translations) he now did with the Bible. From his work on Aristotle he was acquainted with the printing house of Henri Estienne. The interest of his successor, Robert Estienne, in Bible printing is well known. Estienne not only retrospectively claims this as his main occupation in his defense ‘why he left Paris for Geneva’ (Les censures…, 1552), but it is also apparent if one looks at the impressive output of Bibles (partial editions and complete ones) from his printing shop.51 Robert Estienne was one of last students of Lefèvre d’Etaples. They must even have cooperated while Simon de Colines published Lefèvre’s edition of the Latin Bible (1522-1523): at that time Robert was working in Colines printing shop. When Lefèvre stopped editing and printing (1526, when he became tutor of the King’s children in Blois, before retiring to Nérac in 1531 with Marguerite de Navarre) it is Estienne who continues editing and printing Latin Bibles, thus prolonging the effort of Lefèvre to revive the interest in the Bible as the texte fondateur of Christendom, focusing on providing a trustworthy edition of the original texts.52 Estienne’s first project was a text critical edition of the Vulgate (1527-8, continued and perfected in 1532, 1534, 1540, 1546), in which he collated ancient manuscripts of the Bible text (i.e. the Latin text of the Vulgate) with a ‘standard’ version, using symbols to indicate different readings in manuscripts he had found in several libraries inside and outside Paris.53 One of the facts he immediately will have realized is the enormous complexity of this matter. Many issues are intertwined: 1. The Vulgate is not the original text but a translation. 2. The text of the Vulgate is not ‘stable’, i.e. different readings exist. 3. The translation in use is not perfect. And, last but not least, since the Protestants used these elements to attack the foundations of the Roman Catholic Church, it is not at all surprising, that the Faculty of Theology followed his exploits with great attention. The fact that Estienne did not venture into the field of publishing Bible translations into the vernacular, secured him some peace, together with the fact that he was ‘The King’s printer’. And as long as he kept confirming the authority of the Vulgate, only striving to emend that text, he did nothing wrong. A new era began when he was appointed ‘Imprimeur & libraire ès lettres Hebraiques & Latines’ to the King in 1539, even more associating him with the Royal Lecturers.54 It is no accident that exactly at that time he began a series of Hebrew Bibles in-quarto (Biblia mediocri forma, in his own catalogue of 1546)55, appearing from 1539-1544, in which almost every book of the Bible has a title page of its own (bilingual: Hebrew and Latin), while the rest of the book is printed entirely in Hebrew characters. The books were meant to be sold separately, perhaps also a commercial move; testing the market before flooding it. The Bible text is the authorative text (massoretic) as published in the second rabbinical Bible (Jacob ben Chaijim).

remark : (this titlepage copied from the catalogue of the Hebraica Veritas exhibition - Museum Plantin Moretus - Antwerp, image 10b. The Hebrew text reads: The book of the Twelve with 'perush' (=commentary) by Rabbi David Kimhi, meticulously edited by Franciscus Watablus, 'ish notsri' (a Nazarene, a christian) who on the orders of the great king Franciscus, teaches the holy language to his countrymen, printed in the house of Robertus Stephanus in the year 25 of the said king, which is the year 299, abbreviated era, here in Paris the great city and mother of 'Tsarphat' = France ).

Most conspicuous though is the edition of the 12 Minor Prophets. They are printed separately supplemented by the commentary of David Kimhi (printed in round Hebrew characters, the so called Rashi type), while the massoretic text is printed in square Hebrew type. Only these 12 booklets reveal the identity of the compiler/editor: François Vatable, the rest is anonymous. Together with the name of the King and the printer Vatable’s name appears on the title pages, both in Latin and in Hebrew (Rashi type). The chronology of the publication makes clear that these individual prints of the Minor Prophets were the first that were published. They appeared sequentially between 1539 and 1540.56 So, from 1539 onwards an intense cooperation between Robert Estienne and François Vatable can not only be assumed, but is a fact, the latter – because of his scholarship in Hebrew – de facto being the editor in charge of this series.57 This cooperation is further confirmed by the inclusion of a number of illustrations in Estienne’s 1540 Bible in the books of Exodus and 1 Kings (Regum III) concerning the Tabernacle and the Temple. Both general views and details of all kinds of objects are provided and explained. They are no products of an artist’s imagination, but carefully drawn representations based on the indications about measures and material in the Bible self, as is explained systematically below the pictures. The title page and preface proudly announce that they are made on the explicit instruction of François Vatable himself.58 And this is not all; in 1541 Estienne publishes a separate edition of the Pentateuch: Libri Moysi quinque… Cum annotationibus, & observationibus Hebraicis...59 His own textual notes are in the margin of the text, and new scholarly annotations are printed below the text in separate notes. In the preface he explains where these notes come from: the royal lecturers. After having suggested that the initiative of King Francis to institute chairs for professors in the Hebrew language was directly inspired by God himself, he explains that he felt it his duty to let as many readers as possible profit from their insights; and this is how he got them:

“All I have done is to ensure that some of the material collected by hearers of the Royal lecturers should by favour of our typographical art reach those of you who by distance or other obstacles are prevented from hearing them. And to these notes I have added the readings different from the current printed editions, which I took from ancient and correct manuscripts.”

We notice that it is not Vatable alone whom Estienne credits for this notes. In this phrase he also implies Guidaceri and Paradis. This is important since these notes, “quasi in extenso”, are the same as the notes on the Pentateuch in the Vatable bible of 1545.60 Perhaps Vatable is credited with too much. Nevertheless, in tempore non suspecto these notes on the first five books of the Bible are what they are said to be: the fruits of the institution of the Royal readership in Hebrew, now available for everyone who can read Latin. As already mentioned Vatable’s labour on the minor prophets and David Kimhi’s commentary was already published around 1540: Apparently these books met with considerable success in the academic world, since a series of reprints of this Hebrew bible (this time in pocket size – enchiridii forma) appeared from 1543-1546 (13 parts), destined for students to buy and make notes while the professor lectured on these topics. The King must have been pleased with the work done by Vatable, for in 1544 he arranged that Vatable – honoris causa – could remain a bursarius at the collège du Cardinal Lemonier (although according to the statutes he should have left).61 His testament informs us that he had a house of his own (in the faubourg Saint Victor, rue Neuve, which he left to his mother), but that he really lived in the college with the ‘Maitres et les confreres boursiers’.62 In 1543 the same King named Vatable commendatory abbot of the Abbey of Bellozane (in the diocese of Rouen), a title and income he kept until his death on 16 March 1547. Jacques Amyot, professor of Greek at Bourges, inherited the benefice of this abbey. When he in his turn was appointed Bishop of Auxerre, the benefice was given to Pierre Ronsard.63

The quality of his work was not only appreciated by the King, Robert Estienne and his contemporaries: taken together this is the first Hebrew Bible, printed in France. Modern scholarship has compared this edition with its predecessors, the Rabbinical Bible of Bomberg (Venice), which also aimed at a Jewish public and the Polyglot Bible of Alcala which is clearly Christian in its ambit, and concluded that the Estienne editions have a particularity. The vocalization is independent from Alcala, there are cantilation marks; even the reversed ‘nun’ appears and the distinction between open and closed paragraphs are present, both typical for the massoretic tradition. Concerning the ‘qetib-qere’ they are generally signalled using a special sign (°) while the ‘qetib’ is vocalized according to the ‘qere’, however without the ‘qere’ printed in the margin.64 Most particular for this Bible, and exclusively Vatable, is the publication of Kimhi’s commentary on the minor prophets. The way these texts are edited betrays the influence of Jewish publications dating back to the time before the rabbinical Bibles appeared. Kimhi’s commentary (in Rashi-Hebrew) is placed below the units of the Bible text to which it refers. The marginal references to the Bible text are very precise. This edition makes clear that the editor himself had found the commentary of Kimhi very useful for studying the Bible. Finally, compared with the impressive polyglot of Plantin (Antwerp, 1569-1572), edited by Arias Montanus, the Estienne Bible, edited by Vatable (and his team) can certainly stand the comparison.65

The 1545 bible - the 'notes de Vatable'

And now, only now, we reach the Vatable bible of 1545. It is not so special anymore, nor exceptional. It is not the only Bible edition in which Vatable was involved and the notes in this edition are not as original as often perceived. As already mentioned: the notes in the inside margin are Estienne’s (from his previous critical edition of the Vulgate), the notes in the Pentateuch are simply copied from the Libri quinque Moysi of 1541, and thus can be linked to Vatable, but not only to him; the notes present in the Zurich Bible, from which the new translation from the Hebrew is copied (without mentioning the source), are also used by Estienne, not in the Pentateuch (no need), but in other books they were integrated in the annotations.66 The extensive notes on the Psalms incorporate much material from Bucer’s Commentary on the Psalms.67 The notes are generally succinct, philological, trying to explain the text to the not-informed reader, that he may understand. This philological and didactical exercise, which is carried on through the entire edition, makes the 1545 Estienne Bible indeed monumental and explains why these annotations were so widely appreciated, and that their transmission was not even obstructed by the gap between confessions.68

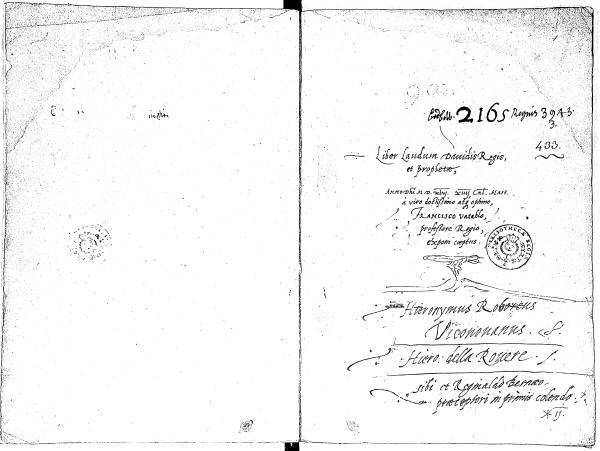

Approaching these notes as if they are Vatable’s is attributing to Vatable too much and too little at the same time: too much because they are not necessarily his, nor all his, and too little, since he did so much more on this field. His participation in the scholarly editions of the Old Testament, in which text-criticism (the establishment or reconstitution of the original text) is so obvious, as is his fascination for the rabbinical exegesis of David Kimhi, is far more relevant than what the notes are or are not telling. Even more: The student notes are much richer than the – necessarily – succinct notes in the Bible. They should not be read only to compare with the notes in the 1545 Bible, but used as a window to look at Vatable in action as the teacher of an entire generation of Hebrew scholars.69 Next to the printed annotations, nine reportationes from Vatable’s lectures are preserved in the National Library of France (Paris). They originate from three different students: Mathieu Gautier (mss lat 532, 533, 537, 538 et 540), Nicolas Pithou (mss lat 88, 577, 581) and Girolamo della Rovere (ms lat 433, f° 1-52).70

the titlepage of this manuscript (courtesy BNF)

Parts of Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, the books of Samuel/Kings are covered by Gautier; parts of the books of Kings, Ezekiel 31-48 and the first six of the minor prophets by Pithou; the folios of Della Rovere deal with the Psalms 1-16. They can – of course – be used to check the authenticity of the notes de Vatable (with the exception of the student notes on the Psalms, which postdate this publication),71 but that is only a minor use; first and foremost they can serve to get a clearer picture of how Vatable lectured. To begin, however, with the minor issue (it is a topic, it has to be addressed): a comparison of these reportationes with the notes de Vatable in the 1545 Bible on the same biblical passages. This has been done by several scholars, but not yet systematically. One of them, Dominique Barthélémy discovered a fourth set of student notes: Bertin le Comte’s. He apparently scribbled (or afterwards transcribed) his notes in the margins and interlinear spaces of a 1528 Pagnini Bible, which Barthélémy was able to find and identify in the Bibliothèque publique et universitaire de Genève. Comparison of these notes with the notes from Gautier and Pithou (Book of Kings) confirmed that these notes were also derived from lectures by Vatable, i.e. they only differ as much as three different witnesses who report the same event.72 The partial results have made clear ‘that the printed and written notes are quite similar, but almost never identical’.73 This conclusion does corroborate the findings of our historical survey: there is Vatable in it, but there are also things in it that are not Vatable’s. Also of little importance, but more interesting, is the question: did Estienne abuse the scholarly authority of Vatable by slipping in some of his own tendentious thoughts? Barthélémy has tried to answer this question. He selected a number of notes that were condemned by Spanish censors (and thus are suppressed in the Vatable Bible of De Portonariis (1584/5) and compared them with the available student notes.74 His analysis makes four things clear, all equally important:

-

Estienne did not invent the notes that rang a bell with the inquisitive minds of conservative theologians, at least not all of them. To prove this one only needs to find one example of a note labelled ‘heretical’, both in a reportatio and in the 1545 Bible. The printed note on Hos. 2:1975 was censured, because ‘iustita’ was explained: as “…per fidem qua iustificantur homines”. The student notes are at least as explicit. Thus Vatable apparently did not hesitate in commenting on this text to underline the importance of faith in the process of justification.

-

On occasion Estienne made Vatable sound more protestant than he was by omitting balancing elements in the notes that were condemned (Joel 2:3276: Estienne printed: “id est. […] quisquis opem a Domino expectarit, credens in Christum.”; Pithou: “Qui fuerint de ecclesia et crediderint in Christum.”). The necessity of belonging to the Church takes out the heresy, which can be read into the note in which only faith (sola fide) is mentioned.

-

Estienne made Vatable sound less conservative than he was in not including plenty of comments in which Vatable showed himself to be ‘a good orthodox Christian’, who is not only aware of the importance of faith and grace, but also stresses the essential role played by the Church in the process of salvation.77 Most of the Protestants also believe this, but will not stress it, because their opponents always did. Where the student notes on Hos. 2,2 repeat over and again that God gathers (Latin: “congregabuntur”) his people “in ecclesia Christiana” [“ac catholica” – Bertin] and that Christ is rightly called the “caput ecclesiae” because the relation between Christ and his Church resembles that of a man and his wife (entirely following the metaphor of Hosea), Estienne sticks to a sober summary avoiding the word ‘ecclesia’, using only the low church term ‘fidelium congregatio’ and even suppresses the entire note in the 1557 edition.

-

Estienne also silenced Vatable by simply suppressing observations made by Vatable during his lessons, which contradicted protestant viewpoints. E.g., in explaining Ezek. 18,19 where the word ‘iustitia’ is crucial, Vatable informs his students that good deeds are an essential element in the process of justification. The student note (Bertin) on Ezek. 18,19 reads: “Iustitia… significat bona opera quae scilicet ex fide profisciscuntur redduntque hominem iustum.” This note de Vatable, which is theologically very interesting, since it tries to keep together what theologians in those days were separating, is not among the notes de Vatable in Estienne’s 1545 Bible.

Although the third and fourth observation operate with what is not printed and thus are endangered by argumentatio ex nihilo, they are to the point, especially since they are corroborated by a lot of circumstantial evidence: Everyone who reads the reportationes without the mind of an inquisitor (and everyone who reads the marginal notes in the Estienne Bible not concentrating on the few that are theologically charged), will notice that these notes are scholarly notes, written by someone who is first and foremost a philologist, trained in and with a passion for reading texts in their original tongues and as far as possible explaining them from their original context (both linguistic and historical). Barthélemy and Kessler-Mesguich78 agree in highlighting in these notes a true interest in the text itself: deciphering words, grammar, syntax, idiomatic elements (like the typically Hebrew modi and tempora of the verbs, as observed by Kessler), always trying to resolve problems, explain obscure places in a way that suits the text itself, looking for an text internal ‘rationale’.79 From my own reading of the reportatio on the Psalms, I can add that the traditional (often christological) exegesis is presupposed and taken for granted.80 In theological matters Vatable apparently remained a true disciple of Lefèvre d’Etaples, whose idea of combining pietas and scholarship, philology and theology, tradition and modernity, he seems to have interiorized, together with his focus on Christ, as the true – literal – meaning of the entire Bible. As in his work on Aristotle, Vatable wanted to improve the edition of texts, help with understanding them properly, and keen on keeping in touch with tradition that has gone before (tralatio nova et vetus), even when the errors and shortcomings in the old translation are not covered up, building bridges rather than destructing bonds.

Nevertheless, this was only the minor issue concerning the student notes and the notes in the 1545 Bible. More important is that they mirror Vatable’s teaching. Here he appears to have been quite serene and very thorough at the same time: Following his lessons provided the audience with a real introduction in and study of the Hebrew text, trying to understand it ‘from the inside’, e mente auctoris, and – and this I will try to show in the last part of this essay – fully aware that the introduction of a Jewish ‘mentality’ was not without consequence for the understanding of Scripture. My thesis is, that exactly because Vatable was so meticulous in his linguistic approach, he must have felt that in the Hebrew language a different worldview manifests itself. Because he lectured publicly, and many of the students of the Theological Faculty attended his lessons, he influenced the outlook on the Hebrew Bible of an entire generation, not only of the Church in France (both ‘protestant’ and ‘roman catholic’, a term only adequate since the Council of Trent (1564)). This explains the inclusion of ‘his’ notes in both protestant (from anglican to puritan) and roman catholic biblical commentaries and compendia.

Student notes (Della Rovere)

When I was trying to decipher the student notes on the Psalms, one of the elements, that I found remarkable, even admirable and advisable, is the way Vatable explained what kind of language Hebrew is, showing time and again how to discern typically idiomatic elements and how to treat them correctly. Although he did not publish a handbook, he showed his students in his lectures ‘how it works’, by – as then was the habit – reading the Bible text in Latin (in his own translation, not the Vulgate, not Leo Jud, not Pagnini), and then verse by verse, sometimes word by word, explaining the nuances, clarifying the difficulties, giving historical and linguistic information if necessary. What is obscured in the printed notes, is overtly visible in the student notes: He cited rabbis, mentioned their names freely (mainly Ibn Ezra, and David Kimhi). As interlocutors they are present. The targum is also called in if linguistic or textual puzzles have to be resolved.81 This rabbinical element deserves extra attention, especially because it is this element which is obscured by the later reception of the notes de Vatable, not only because the names of the Jewish authorities were suppressed (already in the printed Bible), but also because biblical interpretation became mainly a matter of Christian theologians, and less of literary masters such as Vatable, who – as we have seen – was no theologian: he was a man from the Faculty of Arts. I want to give one example of the genius of Vatable. I shall focus on one verse, a detail in the explanation of an idiomatic Hebrew expression present in Psalm 7,5.82 This is the concluding part of an oath, invoking in strong words, emphatically, the punishment that may be inflicted on the man who prays (David according to Vatable), if he is guilty. The translation is quite simple, all words are clear, and once the syntax of the oath is discerned the general interpretation is also clear, but the quite strong expressions used by David, remain puzzling. The Hebrew wording is plastic, vivid:

Let the enemy persecute my soul (nẹp̄ẹš/anima) and take it; yea, let him tread down my life (ḥay/vita) upon the earth, and lay mine honour (kāḇōḏ/gloria) in the dust. (Ps. 7,5 – KJV)

The translations printed in the Estienne Bible do not differ much:

| Nova (Zurich) | Vetus (Vulgata) |

|---|---|

| …persequatur hostis animam meam, et assequatur, et conculcet in terram vitam meam, et deducat gloriam meam in pulverem. | … persequatur inimicus animam meam, et comprehendat, et conculcet in terra vitam meam, et gloriam meam in pulverem deducat. |

The short note in the original edition explains: “i.[id est] mori me faciat vel, ita extinguat, ut nulla mei memoria sit apud superstites et posteros. Memoria iustorum non caret gloria apud homines”. The longer note (diffusiores annotationes and Psalterium duplex of 1546) adds to this phrase: “Hic gloria pro memoria sui posuit.”

Obviously the glossator felt an urge to explain the last two expressions

1. Trampling one’s life into the earth

2. Laying one’s honour in the dust

He explains this metaphorically in a very elegant way: these expressions are florid ways to say: they may kill me (first expression) and even wipe out my memory with the next generations, the added phrase explaining that ‘gloria’ just stands for ‘memoria’. This is, however, not the way François Vatable tried to elucidate these expressions to his students on a day early in 1546. It is the way Leo Jud (or Bibliander) explained this verse with an addition from Bucer’s Commentary. The first part of the note (as the previous notes in this Psalm) is derived from the Zurich Bible (1543). The phrase is reformulated, the content is the same.83 The second part (about the most difficult phrase: “to put my honour in the dust”) mirrors the explanation given by Martin Bucer in his famous Commentary on the Psalms: this is about posterity forgetting your name. Your name = your glory = your dignity, will be lost.84

Although quite satisfying, this is not – according to François Vatable – what these Hebrew expressions really mean. Although difficult to decipher I propose to hear his lesson, as recorded by Girolamo Della Rovere, freely – and hopefully faithfully – paraphrasing his notes.85

May my enemy persecute my soul, or: let him act in this way, that others persecute my soul, my soul, that is: me. My life may be trampled into the earth. He means: “Trampled on the ground my life shall be spoiled, my breath will go out of me, I will die”. Using the expression “trampling my life” the poet uses what we call a ‘pregnant’ way of speaking, in which the word ‘life’ really refers to the ‘body’. So what he really says – not pregnantly but plainly – is: “By treading on my body, I will be deprived of my life”. And he may make my glory… Concerning the use of the term my glory it is important to understand that ‘his glory’ has no other domicile than ‘his body’. Even simpler: It is ‘his soul’ to which he refers when he says ‘my glory’, i.e. that which excels the body. ... to lie in the dust, dust being the same as the earth, this does certainly refer to the grave: “so, when I am thrown to the earth and have died, let him then put me in a grave, bury me.” There are some Hebrews who interpret this as referring to body and soul. They are convinced that the soul of the wicked will perish with his body. You can also think of what we saw a few weeks ago in Psalm 1, where it was said that ‘the wicked will not rise to judgment’. This is of course a heretical opinion.

Thus, having tentatively reconstructed part of a lesson of Vatable, it is easy to see that in this case there is no strong link between this interpretation and the annotation in the Vatable Bible. Even more: the keywords of that interpretation: ‘memoria’, ‘praeterites’ ‘posteros’ are absent; ‘gloria’ is not equated with ‘memoria’. More important though is that we witnessed a true Hebrew exegesis in a lecture by a Christian professor. All elements in this exegesis prove that Vatable really knew that Hebrew was not only a different language with some odd idiomatic expressions, which could be transferred into Latin, and then loose their alterity. In his interpretation the basic anthropological difference between Christians and Jews comes to light; The Jewish view has found a powerful expression in the Hebrew language, in the idiomatic elements of it, mainly the meaning and use of words like ‘nẹp̄ẹš’ and ‘kāḇōḏ’, two almost untranslatable words. They are both related to a basic difference between a Christian (Greek, Hellenist) worldview and a Jewish (Hebrew) worldview. The Christian outlook is basically dualistic: man as a temporary conglomerate of an eternal spiritual essence: his soul, which is captured as long as he lives on this earth in a material mortal body. In Vatable’s days this was still an almost un-reflected presupposition of Christendom. Nevertheless this anthropology (wider: this worldview) is not present in the Hebrew Bible.86 The meaning of the Hebrew word ‘nẹp̄ẹš’ (which is generally translated with anima/soul) has quite different connotations, and certainly does not refer to an ontological entity that exists independently from the body.87 Seen in this light, the explanation of Vatable is remarkable. He sees a close connection between ‘soul’ (anima/nẹp̄ẹš), ‘life’ (vita/ ḥay), and ‘honour’ (gloria/kāḇōḏ). They are all linked explicitly to man’s bodily existence. The effect of his exegesis is that the three statements (certainly the last two) almost become tautological. Also remarkable is Vatable’s straightforward equation of ‘anima mea’ with ‘me’. He stresses the fact that human existence is one, and that words like soul (anima/nẹp̄ẹš) and honour (gloria/kāḇōḏ) are not interesting phenomena an sich, but are only relevant as long as they are connected to the body, and thus to man as he exists, lives, acts in this life. This is also 100% Jewish. Another proof of Vatable’s profound knowledge of the Hebrew world is that he refuses to give the word ‘kāḇōḏ’ any ethereal meaning, as is done by Bucer who equates it with ‘memoria’. Just like the nẹp̄ẹš, the kāḇōḏ can not be disconnected from the body. It has no being in itself. Honour or glory, but now we better replace it with the Hebrew word: ‘kāḇōḏ’, says Vatable, is very much like the nẹp̄ẹš, but in particular it is that which gives human life and activity some ‘weight’, some ‘gravity’ (which is the primitive meaning of the Hebrew word ‘kāḇōḏ’) seen in the light of eternity, or better: coram Deo, in God’s eyes. Vatable goes so far as to practically equate ‘kāḇōḏ’ and ‘nẹp̄ẹš’ (‘anima’ and ‘gloria’), which indeed is possible in Hebrew, but remains very odd in Latin.88 Vatable’s final remark about some Hebrew exegetes who suggest that – at least for the wicked – there is no eternal life at all, but that they simply perish when they die (i.e. their souls perish with their bodies) is of course rejected as heretical, but was– and still is – an opinion which in the Jewish anthropology is quite defensible. Actually, if one follows Vatable’s exposé this opinion does not come as a surprise, but as a logical consequence. His reference to Psalm 1, added in the margin (was there a discussion?) suggests that he understood how and why these Hebrews came to adopt these opinions and how perfectly exegetically logical they were. In 1546 it was however unthinkable to publicly advocate these positions. However, the fact that Vatable was able to expound them so coherently, suggests that he was fully aware of their consistency. And, to make the circle complete: did not Aristotle – now already more than 30 years his companion in philosophia – say something similar concerning the essence of the soul in his De anima?

We should not underestimate François Vatable. He probably had his opinions, but –unlike many of his contemporaries – knew that there are times to speak out and times to remain silent.

Antwerpen, Dick Wursten