Abstract

Based on a historical reconstruction of the ‘Ferrarese imbroglio of 1536’ (a religious scandal in Ferrara involving the Court of the Duchess, Renée de France)), the historiography around this period is deconstructed. Then the focus will shift to the standard biography of Jean Calvin, who visited Ferrara around that time, and whose meeting with the Duchess has achieved canonical status, and whose involvement in the ‘imbroglio’ is routinely recounted. By analyzing the origin, birth and growth of this story, we will proof that it’s a myth serving propagandistic aims. This will finally lead us to a reassessment of the relation (mainly the correspondence) between Jean Calvin and Renée de Ferrare.

Introduction

In April-May 1536, Jean Calvin – only 26 years old – stayed for a short time in Ferrara, probably together with Louis du Tillet, a friend and cleric.1 No one doubts this statement. It’s an established fact. Why he went, what he did, how long he stayed, with whom he talked, is unknown. There is no documentary evidence to fill in the picture with more detail, and Calvin himself never referred to this trip, not even casually. This is also an established fact. It’s only after Calvin’s death, in the sketch of his life by Théodore de Bèze (1564/1565 and 1575) that the trip is mentioned, still without detail, but informing us that he was received by Renée de France, Duchess of Ferrara (1510-1575, whose court at the time was a haven for French refugees suspected of ‘heresy’), and that this meeting made a deep impression on the Duchess. To accept this information at face value, as is generally doen, is naïve. Bèze’s ‘life of Calvin’ basically is an apologetic document, not a ‘biography’.2 More on this below. Nevertheless, a complete mythology has been woven around Calvin’s stay in Ferrara, including vivid accounts of his activity there. This took place mainly in the nineteenth century, but the impact of it is still perceptible today, and not only in popular writing.3 In the leanest version, Bèze’s statement is repeated, generally with the reference that Calvin served as a secretary to the Duchess. In the longer version, Calvin teaches the true religion (often written with capitals), privately in the Chambers of the Duchess, publicly in sermons, attacking the authority of the Pope and denouncing Holy Mass as an abomination, resulting in an investigation by the Ferrarese inquisitor, who arrests a number of ‘heretics.” Calvin himself barely gets away.4 Quite odd, that an event about which hardly anything is known, developed into such an eventful story.

Time for a reassessment, not only because the historical truth has its rights, but also because legends and myths impede the vision of what really happened. To achieve this, I will first summarize the events that took place in Spring 1536 in Ferrara – it wàs an eventful period, well documented and thoroughly researched, but Calvin did not play a part in it. This – I will show – is also an established fact, but scholars seem to have trouble to accept this. After having cleared the field, I will try to reconstruct how it was possible that Calvin was perceived as a prominent agent in the Ferrarese imbroglio of 1536 (in which he did not partake). Taken together this reconstruction/deconstruction will spread new light on the true relation between Calvin and the Duchess.

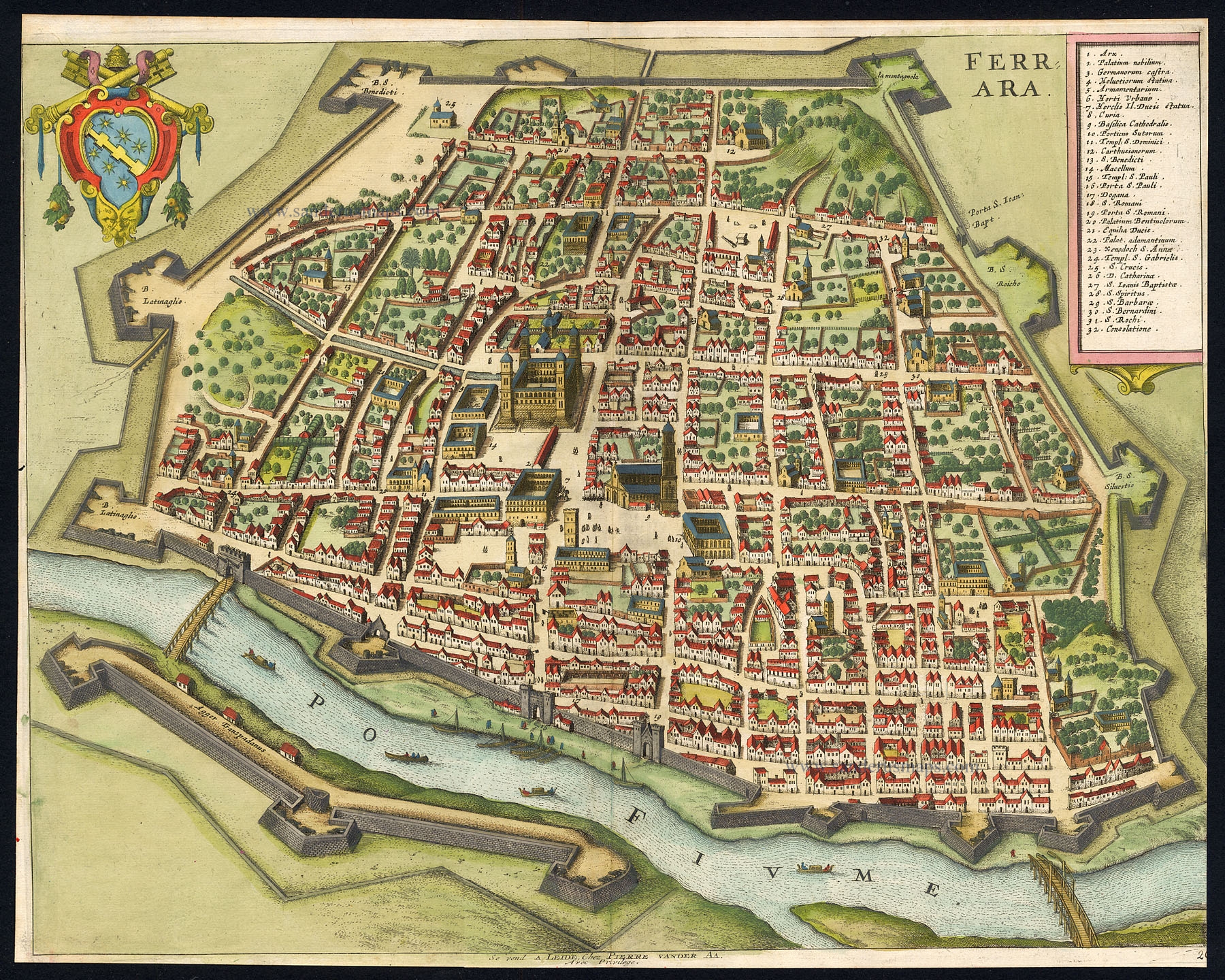

Lent in Ferrara, 1536

Things sparked off in Ferrara, during a religious Service on Good Friday 1536 (April, 14th), when Jehannet de Bouchefort, a singer of the Ducal Chapel left the church ostentatiously just before the Adoration of the Cross took place.5 It caused a scandal, and the local inquisitor (an official of the Duke’s administration) started an investigation. It soon became clear that the French Court of the Duchess was a hotbed of religious free-thinkers (in those days often labelled ‘Lutherans,’ but in reality, there was a wide variety of reformations (plural) going on at that time, both in- and outside the official Church).6 Asked for names, Bouchefort kept his mouth shut. Other witnesses were called and testified to lively discussions in private chambers, intensified during Lent, about issues like the authority of the Church and the Pope, the need for Confession, whether or not man had a free will, etc. all hot topics in the 1530s, and indeed not innocuous from the point of view of the official Church. It soon became apparent that religious refugees from France dominated these discussions. They had left France because of the repression following the infamous Affaire des Placards (broadsheets attacking Holy Mass as the abomination of abominations, October 1534/ January 1535). Although the Duke was aware of this situation, he offered shelter to many of them. Both he and his wife engaged several of them in their own Court. The abovementioned Bouchefort was one of them. Before entering the Ducal Chapel, he was a singer in the Royal Chapel of the King of France (chantre de la chambre et valet de garde-robbe du roi).7 The same goes for the court poet, Clément Marot (enrolled as secretary to the Duchess) and Lyon Jamet (one of the Duke’s private secretaries, at that time on diplomatic mission in Rome). All three figured on the list of ‘criminals, wanted for heresy’ published in January 1535 in France. As a matter of fact, they were sentenced to death by default. Apparently, the Duke didn’t mind, as long as they did not cause any trouble.8 So, together with an ever-increasing number of similar religious refugees, Bouchefort had lived peacefully in the ‘French enclave’ in Ferrara for almost a year, under the high protection of the Duchess and tolerated by the Duke, until that ominous moment during Holy Liturgy, when the singer apparently could no longer reconcile it with his conscience that he had to kneel in front of the cross, saluting it as a salutary object, singing hymns like ‘Pange lingua gloriosa’.9 It must have felt like idolatry, an abomination. And, he was not the only one as the inquisitor found out. People very close to the Duchess seemed to be implicated. One witness mentions the names of two of Madame’s secretaries: Clément Marot and Jean Cornillau. He said that it was common knowledge that these were inveterate ‘Lutherans.” Asked what or who caused this sudden uproot of heretical activity during Lent, the witness referred to ‘a man of the religious order of hermits preaching in Madame’s court.” He added that ‘before this preacher came, the women at court were very devout, but after being exposed to his preaching they hardly wished even to appear pious; they instead began to pass judgment on religious matters, claiming that listening to sermons was a waste of time, as was attending the Office of the Holy Virgin’.10 The account of a second witness confirmed the image of Renée’s court as a breeding ground of free-thinking heretics. This witness adds a physical description of one of the most zealous preachers: ‘a small Frenchman who had received a post as Madame’s secretary.” He is sure that this preacher had the back of Madame’s personal almoner.11 Pressed once more for his name, the witness replied ‘that he had heard he was a religious fugitive from France, and thinks a schoolteacher living in the county of Ferrara might have more information.’12 Various arrests followed and more were to come. Even the position of Renée was threatened. She asked support from her uncle and aunt (François Ier and Marguerite de Navarre) and Anne de Montmorency (the Grand Master of France). They reacted almost immediately. Diplomatic missions by highly skilled French Ambassadors followed each other. They claimed that the Ferrarese Inquisitor had no jurisdiction over French citizens. The Pope was persuaded to join in this game. He issued a ‘Breve’ in which he demanded that the prisoners (or the accused?) had to be tried by an ecclesiastical court, and thus should be transported to the papal city of Bologna. The Duke did not comply, neither with the Pope, nor with the French, resulting in a gridlock. The investigation slowed down, Clément Marot could not be found, and the mysterious ‘preacher from the order of the hermits’ also seemed to have vanished into thin air. The effort of the Duke to collect incriminating evidence from France via his Paris Ambassador (Girolamo Feruffini), proved less than fruitful. Montmorency and the King informed him that patience was running thin. Finally, the Duke gave in, asked and got permission from the Pope to release the prisoners into the hands of the French authorities, and in August 1536 they were handed over to the Viennese Ambassador, George de Selve, Bisshop of Rodez. The dust settled soon. In a joint venture, the French, with support from the Pope, had triumphed over the Duke and his inquisitor.

Religion? It’s politics

What the above account makes clear, is that eradication of heresy (to which all actors were committed) apparently was not the real issue in this Ferrarese imbroglio. If it were, then all parties (the French, the Ferrarese and the Pope, ecclesiastical and civil) would simply have congratulated the Duke on the arrest of some notorious heretics and would have joined forces to have them executed. Instead they all excelled in obstructing each other’s initiatives. What seems a religious imbroglio, is in fact a political showdown. The Pope (Paul III, i.e., Alessandro Farnese) also uses the affair as an opportunity to strengthen his position vis-à-vis the Duke of Ferrara.13 One should not forget that in 1536 the tension between the two superpowers of the day, Habsburg (Charles V) and France (François Ier) rose by the day. A war seemed imminent, and one of the fronts would be in Northern-Italy. The position of Ercole, Duke of Este, was extremely difficult. Through his marriage with Renée de France, he was supposed to be loyal to the French. The Pope on the other hand, used the proximity of the victorious Habsburg Army (returning via Italy after the conquest of Tunis14) to put pressure on him to join the Habsburg League against the French. The French on their side, had already invaded Savoy-Piedmont, and were very interested in Milan. They wanted to be sure of the loyalty of the Duke. In April 1536, many observers were sure that the outbreak of war only a matter of time. In the diplomatic jousting to avoid war and/or to win ground without actually having to wage war, the Pope (Alessandro Farnese) played a crucial role, and – as a shrewd politician – he profited from it. In all this, the Duke was a minor player, caught between the two super-powers, and not able to keep pace with the diplomatic skills of the French and the Pope. In the end he had to comply to a solution concocted between the French Ambassadors and Pope Paul III, regarding his domestic affairs. In 1536, an open confrontation between the two superpowers on Italian soil was averted, but the Savoy region and Turin remained French. It’s in the corridors of this diplomatic tug of war that the Ferrarese imbroglio was both instrumentalized and settled.15 It became apparent that the link Ferrara- France was not tenable anymore, and the Duke – reluctantly – gave up his political independence and joined the Habsburg League. To conclude this episode. After another outburst of ‘heresy’ at the Court of the Duchess in 1541, the Duke banished his wife to a castle in Consandolo (about 15 miles from Ferrara) and the size of her French Court was systematically diminished. Her correspondence was intercepted, and Renée became more and more isolated. Ironically, the return to a more ‘normal’ life was prompted by a visit to Ferrara of Pope Paul III, in Spring 1543. He had to be received and entertained properly and admonished the Duke to recall his wife and live together as a marital couple. In the many vicissitudes of the Duchess, it is remarkable that this Pope (from the house of Farnese) at two occasions contributed to effectively finding a way out (1536) or a modus vivendi (1543) in situations where Renée felt wedged between loyalty to her husband and deeply felt inner convictions (loyalty to France, and to her faith).16

Calvin in Ferrara: the birth of a myth

Considering the facts, one wonders why in the nineteenth Century almost all scholars conducting archival research in Ferrara, made Calvin a main actor in a play of which the script doesn’t even contain his name? The answer is simple. Based on the standard Calvin biography, they were sure he had played a role, so his name had to be in the script. They simply hadn’t found it… yet. Historical research is a complex exercise. There is always more context than one is aware of, and at the same time many of the relevant facts are unknowable, both on the level of the factual history itself (we don’t know all the relevant facts) and on the level of interpretation (we can’t look into hearts and minds of people: what were they really thinking, feeling, experiencing?). However, without an interpretation, all facts and texts remain mute. So, one has to risk an interpretation, starting with the knowledge one has, while constantly being aware that the margin for error is immense. It is clear that in this case, something must have gone wrong. Therefore, it might be useful to start from scratch, trying to differentiate between fact and fiction, and then try to find out what these scholars overlooked, didn’t know, or mis-interpreted.

The facts

Calvin was in Ferrara. That’s certified, nòt because the trip is mentioned in all accounts of Calvins’ life – that’s no guarantee (they were written after Calvin had died in 1564) – but because there is an independent eye-witness The Ferrarese physician and Professor of Medicine, Johannes Sinapius.17

1. An eye-witness

In a letter, dated 1 September 1539, Sinapius refers to their first meeting in Ferrara in 1536. The letter is a eulogy on Calvin’s qualities as a spiritual mentor, friend, and – surprise – marriage broker. In it he expresses his wish to meet Calvin again, and then writes:

Certainly, at the time when you were here, a few years ago, you actually concealed yourself from me like the Silenus of Alcibiades.18

The reference to Alcibiades’ Silenus evokes a passage in Plato’s Symposium, where Alcibiades compares Socrates to a Silenus, on the outside ugly and unattractive, but on the inside full of godly treasures. This comparison tells us that at the time of their meeting in Ferrara, Sinapius had no clue that he was talking to someone special. This is not surprising. In 1536, Sinapius was a professor of Medicine at the University and personal physician to the Duchess of Ferrara, an insider so to speak. Calvin was a visitor, not yet known as a writer and theologian, travelling under the pseudonym of Charles d’Espeville.19 Apparently, he did not present himself prominently. Unfortunately, Sinapius doesn’t mention a date. However, this can be reconstructed.

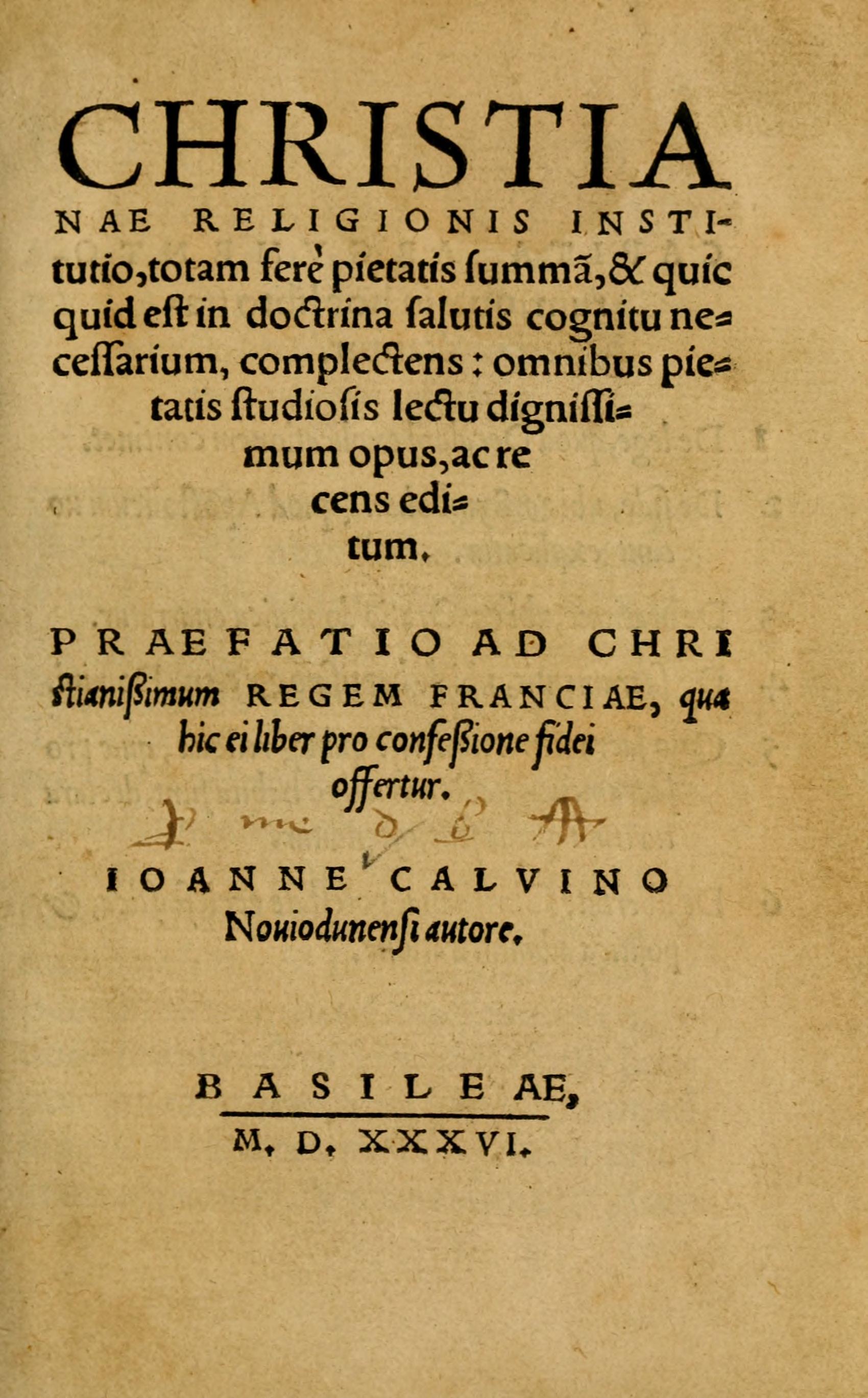

2. The timeframe

Based on two certified dates, we can say with certainty that the trip must have taken place between 15 March and 12 June 1536. The first date (terminus post quem) is based on the fact that in March 1536 Calvin was in Basel, assisting at the preparations of the first edition of his Institutio, published by Thomas Platter d.d. 15 March 1536. In a semi-autobiographical section in the Preface to his Commentary on the Psalms (published in Latin in 1557, in French in 1558),20 Calvin informs the reader that he left Basel immediately after having finished the work on the Institutio (‘discessu brevis,’ ‘incontinent après’). 21 Unfortunately, he doesn’t say where he went. The second date (terminus ante quem) is also established. On 12 June 1536, he is in Paris with his brother Antoine to arrange family affairs.22 After subtracting the time needed for those quite long journeys, it seems plausible to accept a stay in Ferrara somewhere in April and/or May 1536. The duration cannot be determined.

3. A timid intellectual?

In the same context (Preface) Calvin explains his motives for the publication of the Institutio in 1536. Only 26 years of age, a licentiate in law (since 1532), he had exiled himself from France and had no regular job. Theologically he was an auto-didact. In the Preface he explains he wrote this book as an apology for those who were persecuted in France, because of the repression following the Affaire des Placards.23 This is also why he addressed the dedicatory Epistle, preceding the first edition of the Institutio, to the French King. Calvin saw it as his duty, as an intellectual, to take their defense. This had nothing to do with vainglory. To demonstrate his humility, he tells that even in Basel he never aired that he, John Calvin, was the author of that book. He lived a hidden life, there.24 This is – still according to Calvin in his Preface – the reason why he left Basel ‘immediately after’ the Institutio was published, and why he kept concealing his identity ‘everywhere else until he arrived in Geneva,’ where he was engaged by Guillaume Farel to become a ‘minister’ of God’s Church.25 This is the moment when he ceases to anonymous and comes into the spotlight. The ‘everywhere else-until’ includes his stay in Ferrara. So, in Ferrara, he was not a self-confident preacher, not the Reformer he would become, but a young scholar, travelling under a pseudonym (Charles d’Espeville), who wanted to write books explaining the gospel to defend the faithful against calumny. That is the maximum one can say about ‘young man Calvin.” It appears that he was still ‘waiting’ to see what God had in mind for him. After Ferrara, things began to move very quickly. After having settled his affairs in Paris (June 1536) 26, he tried to return to Strasbourg to continue his life. He imagined it to be a tranquil and studious, serving the faithful with his brains.27 Things turned out differently: ‘His job found him in Geneva.” There he became a teacher (‘professor’), and a little later a preacher. It will take some more years (roughly from 1540 onwards) before he really emerges as one of the leaders of the Swiss and French Reformation.

This simple sketch of the young Calvin makes it quite unlikely that he in any way was actively involved in the Ferrara imbroglio, even though it is not impossible that he was in Ferrara during that time. He was too ‘bashfull and timid’ for this kind of actions.28 And – even then – if he had participated, Sinapius certainly would have remembered it and Calvin himself would have had no reason to be ashamed of mentioning it. On the contrary, he would have used it in his ‘image-building’: ‘Already as a young man I confessed to the Truth and suffered for it.” Quod non. Although argumenta e nihilo should be distrusted, this one seems not inappropriate.

The Life of Calvin (Bèze)

The next references to his trip can to be found in Bèze’s (and Colladon’s) posthumous accounts of Calvin’s life. The earliest account is written by Bèze in 1564, shortly after Calvin’s death. Bèze relates the story, beginning with the year 1534. It is clear Bèze is familiar with Calvin’s own account of this episode in the Preface to the Psalms. The framing is similar, but Ferrara is now explicitly mentioned as a destination and some details are even given, of which the relevant ones are italicized below:

Therefore, he left France in 1534 and in this same year had printed in Basel his first Institution as an apology addressed to the late King François, first of that name for the poor persecuted faithful upon whom was wrongly applied the title Anabaptists, to excuse in the eyes of the Protestant Princes the persecution to which they were subjected.

He also made a trip to Italy where he saw Madame the Duchess of Ferrara, still living today thanks to God, who, having seen and heard him from then on knew him for what he was, and ever since up to the time of his death loved and honored him as an excellent agent of the Lord. On his return from Italy at which he only glanced, he passed through this city of Geneva...29

Although Bèze says that Calvin stayed in Italy/Ferrara for only a very short time (‘Italy, at which he only glanced’), he does suggest that Calvin actually met with Renée de Ferrara and that this meeting was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Even more, already then the Duchess recognized Calvin’s authority as a god-sent man (‘excellent organe du Seigneur’). But now we must be on the alert. As already signaled, Bèze is not a biographer in the modern sense. He is Calvin’s successor, and France is torn apart by the religious conflict on how to re-build and govern the Church of God. Many factions were struggling for power. Signs were there that the conflict might take a violent turn. We are on the brink of the French Wars of religion.30 The pamphlet press flourished. So, writing that John Calvin died a godly man (this is the main message of the first ‘Vita’) was not simply a matter of supplying the population with correct information. It was a strategic move in Geneva’s public relations policy in which Calvin is not a saint (God forbid!) but a man who lived an exemplary life, and whose vision of the Church was God-inspired. The biographical elements, Bèze adds to this account, serve to underline that Calvin ‘practiced what he preached,’ and that people willingly or unwillingly recognized his authority. The reference to Ferrara is part of this apologetic offensive in propaganda warfare. Bèze is a spin-doctor. Everyone in France knew who Renée de Ferrara was and what she stood for. Things in Ferrara had gone from bad to worse, especially since Ercole and the new order of the Jesuits had joined forces. In 1554 the Inquisition had filed a complaint for heresy against Renée. To save her life, she had to publicly take Holy Communion. After the death of her husband (1559), she had returned to France and withdrawn to her castle in Montargis, transforming her Court once more in a safe place for persecuted people, not discriminating regarding the cause of persecution (much to the irritation of her spiritual adviser, Jean Calvin). That this formidable woman respected Jean Calvin is a signal that the Reformed faction has support in high places. Moreover, it was true. Renée valued Calvin’s advice, although she did not always follow his lead. However, - and this is what we are looking for - this does not imply that their relationship started with an actual meeting in Ferrara in 1536, as Bèze suggests.

Already in 1565, a new edition appeared, this time probably in collaboration with Colladon.31 In this edition we read that Calvin went to Italy with a companion, whom the context reveals to be Louis du Tillet.32 The last and definitive edition of Bèze’s Life of Calvin was written in Latin and published in 1575. It’s far more detailed than the earlier editions. New and noteworthy elements from this Vita are italicized below:

Calvin, after publishing [the first edition of the ‘Institutio’], and thereby, as it were, performing his duty to his country, felt an inclination to visit the Duchess of Ferrara, a daughter of Louis XII, whose piety was then greatly spoken of, and at the same time to salute Italy as from a distance. He accordingly visited the Duchess, and, in so far as the state of the times permitted, confirmed her in her zeal for the true religion. Therefore, she valued him very highly while he was alive, and having survived him, she also gave a brilliant example of how grateful she was having known the deceased.

He left Italy, which he – as he used to say – ‘had only entered in order to leave it,’ and returned to France…33

Interesting elaborations: For the first time Bèze suggests that Calvin went to Ferrara with a plan: meeting the Duchess. (‘felt an inclination to visit the Duchess’). The wording of Renée’s appreciation is extended with the intriguing statement that Renée gave a brilliant example of her gratitude towards Calvin, even after he had died (1564). As with the previous elaborations it is highly unlikely that suddenly new information had popped up. Bèze is still a spin-doctor and probably only tries to enhance the basic idea of Calvin being Renée’s spiritual mentor to drive his message home. He claims that Renée not only was grateful for, but also remained faithful to Calvin’s advice until her death (June 1575). The ‘brilliant example’ might also refer to her Testament, in which she prohibited burying her with any pomp and circumstance, be it royal, be it ecclesial. The phrase itself replaces the previous statement that ‘the Duchess, who is still alive’ cherished Calvin’s advice. Often overlooked are two other additions. The first stipulates that Calvin not only wanted to visit Renée, but also wished to salute Italy as from a distance. No great plans, nothing definitive. The second addition is the introduction of a quote of Calvin, referring to his stay in Ferrara (“He left Italy, which he – as he used to say – ‘had only entered in order to leave it’”). These two phrases replace the previous statement about ‘Italy at which he only glanced.” In content they are interchangeable: Calvin was in Italy only for a very short time, and was not particularly fond of it. However, the fact that Bèze introduces this appreciation as if he quotes Calvin, gives more weight to the conclusion. Although unverifiable, the quote might be authentic, especially after the deconstruction the myth. In the end, this might well be the most correct factual description of Calvin’s visit to Ferrara: He was there, he did not like what he found, and he left.

It is clear what Bèze is doing, perhaps unconsciously. He uses elements from the later relationship between Renée and Calvin, and projects them to the supposed beginning of their relationship in Ferrara 1536. This procedure will be copied again and again in the 19th Century, making it possible that the young Calvin became a central agent in the Ferrara imbroglio of Lent 1536.

The myths revisited

After having cleared the field, it’s time to revisit the myth about Calvin in Ferrara and take a fresh look at how Renée and Calvin came into contact (and what their correspondence really is about).

Calvin in Ferrara

It’s clear that in his Vita Bèze sowed the seeds for the creation of the myth: Calvin might have saluted Italy from a distance,’ but he went to Ferrara with the explicit purpose to meet the Duchess. And when they meet, the Duchess is so impressed – according to Bèze – that it became the beginning of a lifelong friendship, in which Calvin played the role of mentor and spiritual coach. As demonstrated above, the relationship between the two is not fictional, but the rest is. However, it is easy to imagine how this myth can begin to grow, in particular when Calvins’ star begins to rise in the era of Reformed Romantic historiography: The hero of faith, the mentor of a woman of royal offspring, whose life captures the imagination. And this scheme delivers even better, when it is combined with the Ferrarese imbroglio of 1536, in which he can play a heroic role. Remember: Neither Calvin nor Bèze ever mention the Ferrarese imbroglio, let alone that Calvin played a part in it. For storytellers however, this combination offers the advantage that there is something ‘to tell.” Basically, this is what Merle d’Aubigné so virtuoso did in volume V of his Reformation History (see note 4). The only problem, as we saw, is that Calvin is not mentioned in that script. Well, this is what we know, now. This is not what a nineteenth Century researcher knew. He honestly believed that Calvin was in Ferrara and played a role in the imbroglio. Origin of this conviction might well have been a casual remark by Ludovico Muratori, an eighteenth-century Modenese historian (Annalist of the Vatican and Estense archives). Writing about the events of the year 1536, Muratori says:

According to the Annalist Spondano, the arch-heretic John Calvin (who in the previous year had come to Ferrara and has lived there undercover) infected Renee, daughter of Louis XII and Duchess of Ferrara, in such a way with his errors that no one could draw the venomous poison from her heart. But in this year this wolf was exposed and has taken refuge in Geneva. I am assured by one who has seen the acts of the Inquisition in Ferrara that this pestiferous troublemaker was put in prison; but while he was being conducted from Ferrara to Bologna he was set free by armed men.34

The first part of the statement echoes the standard story of Bèze (albeit in the jargon of a Roman Catholic), the second part triggered a lot of historians to start an investigation. To no avail; the mysterious document could not be found. The one who really cloaked himself in this matter, is Bartolommeo Fontana (1835-1901), who searched all the archives to find evidence that Calvin really was there and was implicated in the imbroglio.35 Although he also did not find that piece of evidence, damage was done. Calvin was ‘smuggled into’ the heart of the Ferrarese imbroglio. The fact that in the other documents, dug up by Fontana and others, some people remain unidentified, gave the historians and novelists plenty of opportunity to fill in names: ‘the hermit who so zealously preached,’ that must have been Calvin. ‘Calvin was no hermit’; No problem: ‘he might have disguised himself as a hermit.” Not convinced? Well, what about that ‘little Frenchman, who was also secretary to Madame’?36 In the last decades of the nineteenth century, a true French-Italian ‘Historikerstreit’ ignited, in which both parties, notwithstanding their disputes, agreed on two things: 1. Calvin dìd play an important role in the Ferrarese imbroglio of 1536, and 2. He had a huge influence on the Duchess. They only disagreed in the evaluation of these events. With Protestant historians this is the story of their hero, the herald of the True Faith, who does not yield to enmity and persecution, and in the end (with or without imprisonment and subsequent narrow escape), triumphantly returned to Geneva. For Roman Catholic historians the same elements form the story of the ‘arch-heretic’ John Calvin, who corrupted the Duke’s wife with his perverse teachings, and – unfortunately – managed to escape. Much havoc could have been prevented, had he been brought to trial then, they implicitly say. Since theological opinions are often connected with deep emotions, it does not come as a surprise that differences of opinion were not perceived as a signal that it’s time to reformulate the research question. On the contrary. One fantasist life is placed over and against the other. Both parties dug in deep and a trenches warfare began. On this point the nineteenth century in many ways echoes the sixteenth, in which the publication of Bèze’s account of Calvin’s life provoked the publication of another ‘Life of Calvin,’ not to celebrate the exemplary life of a godly man, but to utterly and totally destroy that image, using all literary means available. I am referring to Jerome Bolsec’s ‘anti-vita’, Histoire de la vie, mœurs, actes, doctrine et mort de Jean Calvin, jadis grand ministre de Genève (Lyon, 1577). With this book, Bolsec, a Carmelite who had converted to Protestantism, earned a living as physician, studied medicine in Ferrara (and for a while was personal almoner to Renée de Ferrara) settled an old score with Calvin, with whom he had fallen out on the topic of predestination in 1551. He had experienced how the ‘timid’ Calvin could change in a ‘bulldog,’ when he felt personally attacked. This ‘anti-vita’ has more of a satire than of serious historiography but was read by many a Roman Catholic as the pure and simple truth about Calvin. It was republished many times in the sixteenth and seventeenth century and re-edited with annotations several times in the nineteenth century.37 Muratori certainly knew it, and in his novella Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt (1936), Stefan Zweig is still tributary to Bolsec.

Renée and Calvin

Only one topic remains to be addressed. If Calvin and Renée did not meet in Ferrara, how did they get acquainted, when did their correspondence begin, what issue triggered it? With the new arrangement of facts, after the ‘deconstruction of the old myths,’ with the towering figure of ‘the Reformer’ out of the way, other people become visible. Renée’s courtiers, and in particular her Ladies-in-waiting. They were not docile followers, but ‘agents.” They thought for themselves, they acted, they even took risks. Not only the inquisitor, but also the Duke finds it difficult to cope with this phenomenon. And, next to the courtiers, there are the scholars of Ferrara University, the painters, the poets, the musicians. In the first half of the sixteenth century, Ferrara still is a thriving Renaissance city. So, it will not come as a surprise that these men and women, who corresponded with the entire world, also were perfectly capable to contact Calvin, if they had questions or wanted his advice. But in this case, we can even be more precise. We know who contacted John Calvin, and we also know the occasion on which this happened.

In the archives of Geneva, a draft of a letter by Calvin for Renée is kept. It is not dated, but it’s clear that this is the first time Calvin writes to the Duchess.38 The fact that Calvin in this letter not even casually refers to a previous meeting in Ferrara, or to the tumultuous events that had happened there, is notable. For us, this does not come as a surprise: They had not met, and for Calvin his stay in Ferrara was not a memorable event. But it did – of course – trouble historians, in particular those who supported an early date for this letter (Summer 1537, very close to the events), especially if we begin to read this letter: Calvin feels impelled to go into great lengths to justify that he dares to write a letter to the Duchess. This makes it even more improbable he ever spoke with her before, let alone that Renée had already accepted Calvin as her spiritual guide, as Bèze claimed in his Vita.39 Exit myth, one would say. However, the possibility of a falsification of a cherished theory not only causes stress but can also lead to cognitive dissonance. To overcome this nagging feeling that something is not right, many interpreters took resort to a kind of ‘close reading’ to press the text to say the things they wanted to hear. They – of course – honestly believed that they only made explicit what was implicit. One phrase in particular seemed amenable for this purpose, a phrase at the end of the first paragraph, part of the ‘captatio benevolentiae.” Calvin writes: “I have observed in you (J’ay congneu en vous) such fear of God and such disposed faithfulness of obedience that….” This quite general observation is then interpreted as a reference to their meeting in Ferrara 1536.40 The English translation of ‘connaître en vous’ with ‘to observe in you,’ already gets one off on the wrong foot, suggesting physical proximity. A more neutral translation like ‘I have known in you’ (meaning ‘I know you to be,’ or even more straightforward ‘I know that you are god-fearing etc...’) does not imply that personal meeting took place. It was common knowledge that the Duchess was a pious woman. The phrase itself is a perfect build-up in order to remind the Duchess of her duty as a Christian princess to act according to God’s will, which Calvin as a chosen minister of God, is going to reveal to her.

It’s a well-known and often cited letter. The issue at stake is very similar to the issue for which Jehannet de Bouchefort and Jean Cornillau had risked their lives during Lent 1536 in Ferrara: attending Holy Mass (even more surprising Calvin does not refer to the events in Ferrara, not even in passing). I paraphrase the question first, because it is easily misunderstood. Protestants and secular historians often have great difficulty understanding the proper meaning of terms like ‘ouïr la Messe’ ( = attend Mass) and ‘faire communion’ (take communion, receiving the Host). In those days, the laity generally participated only ‘by proxy’ in the rite of Holy Communion. The Priest and the Deacon performed the ceremony, the latter representing the people during Communion, the former acting on behalf of God. So, one can perfectly ‘attend Mass’ without ‘taking communion/receiving the Host.” 41 The question at stake in Ferrara is, that Renée and her court did attend Mass but apparently organized a kind of private service afterwards in which they ‘took communion.” It’s not entirely clear how this was organized, but they viewed this as a celebration of the ‘Lord’s Last Supper.” François Richardot, Madame’s almoner, had claimed that this indeed was the proper thing to do.42 One of the ladies-in-waiting, however, had refused to attend Mass.43 The Duchess had withdrawn her goodwill from the lady and warned others not to cause scandal. The history of Jehannet de Bouchefort seemed to repeat itself and this time the Duchess was determined to nip it in the bud, much to the dismay of Madame de Pons (Anne de Parthenay). In one way or the other (by Letter or via-via, many people from Ferrara passed through Geneva on their way to France or the Upper-Rhine cities), she had informed Calvin about the situation and asked him to address this question, suggesting that the Duchess was also eager to hear his opinion. This is the question that Calvin is going to address:

Is it allowed for a biblically informed Christian like the Duchess (and many of her courtiers) to hear Mass (attend the service, listen to the words of the consecration, see the elevated Host, kneel etc.) and then afterwards in a way ‘take communion,’ which serves as a celebration of the last Supper of the Lord?

Calvin’s answer is simple: The Mass is an abomination and attending Mass is a sacrilege (the wording used by Calvin, echoes the wording in the Placards of 1534 and the Epistolae Duae of 1537)44, so it is simply forbidden for a Christian to attend it. Richardot is wrong, and the lady in question does not deserve scorn, but praise. This is strict position: Not only the ‘taking of communion’ (receiving the consecrated Host) is out of question, but being present when others do that, is also considered a sin. One is ‘guilty by contamination’ (a word that Calvin uses a lot, almost in a literal, physical sense, also a favorite with inquisitors: heresy as contagious illness). So, Calvin strongly advises the Duchess not to listen to Richardot. He is a hypocrite, corrupt, money wolf, and a completely untrustworthy person (When people disagree with Calvin, he always takes this personal, and reacts with vehement attacks ad hominem.) He urges the Duchess to take a firm stand, and reject the Mass, openly and totally. To do this, is a holy duty for any god-fearing woman, and a divine calling for a Princess. Renée’s reaction to this letter is unknown, but it can be inferred from her actions. Richardot remained in service, and this until 1544.

Conclusion

Some reticence (caution) seems advisable, when one addresses the relationship between Calvin and Renée. Seen from Renée’s side (the first one dating from 1553, asking Calvin for suitable husbands for two of her ladies in waiting45) there is respect, certainly. He is a spiritual guide, yes, but only up to a certain degree, and with whom she argues, if she doesn’t agree with him. And he certainly did not have monopoly on advice. Labeling their relation as a ‘close friendship,’ is incorrect. The characterization is from the wrong ‘category.” It’s not sentimental. Calvin is a man with a mission, and he corresponds with a woman who has power, related to the French king. He needs her more, than she him. In this respect, the first letter is telling. In nuce all Calvin’s letters are there. As a thread through his entire correspondence run the words spoken by the prophet Elijah urging the people of Israel to take a stand, to choose: “How long will you go limping between two different opinions? If the Lord is God, follow him; but if Baal, then follow him.” (1 Ki. 18,21).46 The topics might change over the years, the scope is the same: Duchess, stop dissimulating, take a stand against the abomination, profess your ‘Protestant faith’ and denounce the Church of the antichrist, the Pope. In short, become a member of my party. That is what God expects from you. When in 1554 the Duchess is – literally – pressed by the Jesuits and the inquisitor to publicly ‘receive communion,’ he is very disappointed and angry that she succumbed to the pressure. He castigates her verbally in his next letter (February 1555), of course ‘with love’ and for the best, that she may repent.47 The summative conclusion by Charmarie Blaisdell, who devoted a separate study to Calvin’s correspondence with ‘women in high places,’ might suffice:

“Of all Calvin’s letters to women, his letters to Renee most closely resemble letters of spiritual counsel… Yet, in Renee’s case too, his political motives seem obvious: he worked to keep her along the straight and arduous path to the Reformed faith for the purposes of keeping the movement alive in Italy and establishing the Reformed church officially in France. Again and again in Calvin’s letters to Renee, we see him become impatient and exasperated with her reluctance to profess openly her Protestant beliefs. 48

In the end his interest in Renée – as in all other women (and men!) in high places – was not personal, only occasionally pastoral (this he left to the ministers, he sent from Geneva), but always political. The way Bèze in his Life of Calvin used the link between Calvin and Renée, corresponds exactly with how Calvin himself viewed this relation, useful for the propagation of the Reformation.

Selected bibliography

Separate document