Alain de Lille: short biography

ca. 1528 - 1202/3

Hardly any fact about the life of Alanus ab Insulis (French de l'Isle = de Lille, from Lille) is completely sure. Even his origin of Lille is questioned by some scholars. One of the main reasons of this uncertainty is the circumstance that there were many Alans (Alain - Alanus) who were active and (more or less) famous in the 12th and 13th Century.

Thus, Alain de Lille has been confounded/merged with Alanus bishop of Auxerre, and with Alanus abbot of Tewkesbury, to name only the two most famous confusions. This implies that certain facts of their lives have been attributed to him, as well as some of their works. To add to the confusion, one of the leading scholars today (Françoise Hudry) advocates that Alanus of Lille and Alanus of Tewkesbury indeed were one and the same person. In such circumstances it seems prudent to abstain from conjectures and accept the uncertainty. Especially since a consensus about the generalities of his life and (main) works is still possible.

It is generally accepted that Alain attended cathedral schools in Paris (probably) and Chartres (almost certain). He thus studied under - or was influenced by - masters like Pierre Abélard, Gilbert de Poitiers, and Thierry de Chartres. One can infer this from the autobiographical aspects of John of Salisbury's writings, a nearly exact contemporary of Alain (parallel lives). Alain's earliest writings date from the 1150s. He is supposed to have taught in Paris, but he also was active in southern France (Montpellier: Alanus de Montepessulano - attested fact), and this into his old age . Generally he is believed to have retired to Cîteaux, where he died in 1202/1203.

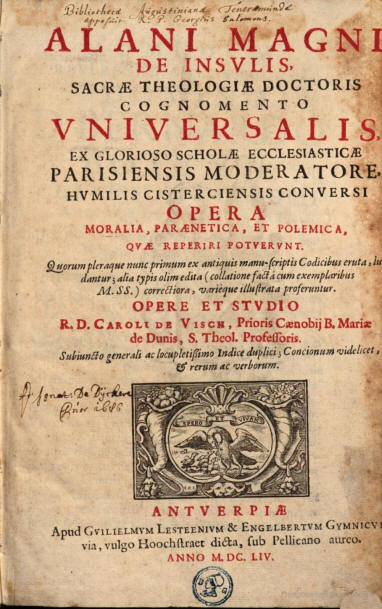

In 1482 a tomb was erected above his grave, with his name and some other texts (see this page), adding/causing lots of confusion because on this tomb 1294 is mentioned as the year he died. The tomb was destroyed but in 1960 the grave was discovered during excavations. Already during his liftetime he had a widespread reputation. His general knowledge caused him to be called Doctor Universalis. Many of Alain’s writings can't be dated with any precision, and the circumstances and details surrounding them are often unknown as well. Legends (generally about his encyclopedic knowledge) circulated during his lifetime and multiplied after his death. In 1654 a general edition of Alanus works appeared in Antwerp: Alani Magni de Insulis... Opera moralia, parænetica, et polemica. The historiographer, abbot of the 'Ter Duinen', Carolus de Visch was the editor. As far as I can see, the Migne edition (Patrologia Latina, vol. CCX, 1855) discusses De Visch' edition, mainly focussing on the identification of Alain, but did not change much (nothing?) in editing the works.

Next to being a

polymath, he was poetically gifted. Two poems attract attention until today:

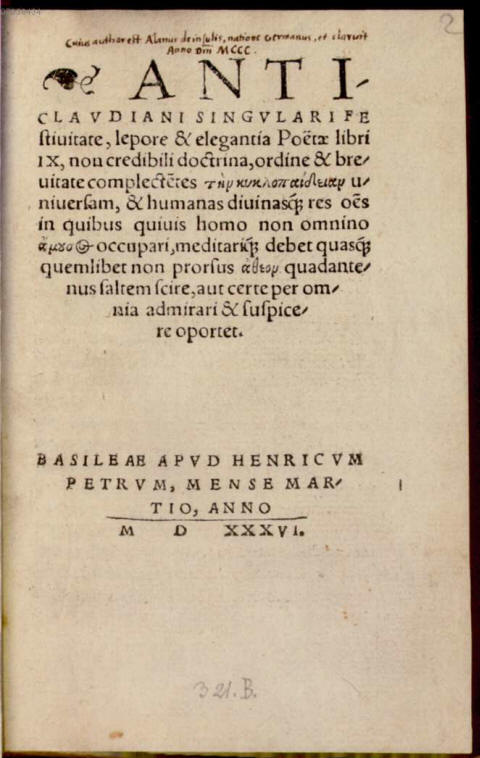

The De planctu naturae is an ingenious satire on the vices of

humanity. The Anticlaudianus, a treatise on morals as allegory, is a

conscious 'parody' of the pamphlet of Claudian against Rufinus. Both reveal

a familiarity with old Greek/Roman literature and extensively use pagan

imagery. Below the titlepage and the beginning of this poem from a 1536

reprint from Basel, [VD16 A 1216], digitized by DFG, München, available via

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

Text and translation of a hymn about the 'vanity of life': Omnis mundi creatura (see below for a modern 'soundscape' (medieval electro)

Full text and translation of the book De Planctu Naturae

Text and translation of the 'Conductus' or 'Rhytmus' De Incarnatione

The most up-to-date and balanced info on Alain de Lille can be read on the French Wikipedia

Over Alanus (Alain) uit Lille/Rijsel is weinig bekend, behalve dat

hij zijn studies waarschijnlijk in Chartres heeft gedaan en dat hij

professor in Parijs en Montpellier is geweest. In elk geval stond

hij in hoog aanzien bij zijn tijdgenoten (als een 'allesweter',

doctor universalis). Hij heeft veel boeken geschreven waaronder een

verhandeling tegen de ketters (m.n. de Katharen/Waldenzen, de Joden

en Mohammedanen). Zijn theologie is een voor die tijd typische

combinatie van rationeel-logisch denken (scholastiek,

propositieleer) en fantasierijk mysticisme (Neo-Platonisme en Stoa).

Zeer bekend is zijn ‘klacht van de natuur’ (Liber

de planctu naturae), naar men zegt van grote invloed op

Chaucer als die dezelfde persoon (Nature) opvoert in zijn

Parliamant of Fowls. Idem voor de Middeleeuwse ‘romans’, als

Roman de la rose van Jean de Meung. Virtuoze beeldspraak in

(metrisch) proza vol personificaties, waarbij de ene verglijking

over de andere tuimelt. M.n. de stijlfiguur van de opsomming bereikt

grote hoogten (toen zeer bewonderd, later vooral verguisd). In onze

milieu-bewuste, maar tegelijk ook erg natuur-onvriendelijke tijden

heeft deze klacht nieuwe aandacht gekregen, hoewel de meeste moderne

lezers wrsch. zullen afhaken als ze lezen hoe de dichter als de

Natuur aan hem verschijnt met de deur in huis valt en z'n beklag

doet over allerlei vormen van tegen-natuurlijke seksualiteitm.n.

homosexualiteit.

Beter in de markt ligt het lied ‘Omnis Mundi Creatura’. Het wordt vaak geciteerd als het gaat om het Middeleeuwse wereldbeeld (hoe lees je 'het boek der schepping'). Prominent aanwezig is het in Umberto Eco’s de Naam van de Roos waar Alanus als autoriteit ook verschillende malen vernoemd wordt. Dat het vooral bedoeld is als een overpeinzing van de 'vergankelijkheid der dingen' vergeet men soms.

Het lied is aan een zoveelste leven begonnen sinds Helium Vola (muziekgroep, genre: medieval-electro-experimental-rock) er een soundscape voor maakte.

Hier een vertaling (zonder pretentie van juistheid, gewoon wat ik ervan kon maken...) en een verzameling van Engelse en Duitse metrische vertalingen. De dichter speelt met taal, dat is wel duidelijk. Basisgegeven is dat de natuur gelezen kan worden als een 'boek', waarin onze natuur wordt geschetst (vergelijk artikel 1 van de Confessio Belgica e.v.a.): een spiegel. Als voorbeeld neemt Alanus de roos, die wel schoon bloeit, maar voor je er erg in hebt, verwelkt, verdort, vergaat. "Zo is ook der mensen leven...". De kernbeeldspraak is dus Psalm 103/1Petrus: Denn alles Fleisch es ist wie Gras... (Brahms). Zie ook nog Job 14. Het werkwoord floreo/flos biedt natuurlijk veel mogelijkheden. De roos als Vanitas-voorbeeld, 'topos', gaat terug op de klassieke oudheid, m.n. Ausonius en is ook na Alanus nog een lang leven beschoren (zie deze pagina), denk bijv. aan Ronsard. Bij Ausonius overigens aanleiding tot carpe diem! Aan het eind van dit lied - voorzover ik het begrijp - wordt dit beeld vermengd, verdiept met de bijbelse notie dat de dood de 'straf is op de zonde' (stipendia peccatium mortis, Rom 6:23) waardoor er een ethisch-morele component in de meditatie sluipt. Ook de opvatting van Paulus dat 'wij onder de wet besloten zijn' (Gal. 3:23, m.n. het spel met het woord: conclusio (sed conclusit scriptura omnia sub peccato ut promissio ex fide Iesu Christi daretur credentibus prius autem quam veniret fides sub lege custodiebamur conclusi in eam fidem quae revelanda erat - voor de niet-latinisten: Doch eer het geloof kwam, waren wij onder de wet in bewaring gesteld en zijn besloten geweest tot op het geloof dat geopenbaard zou worden) speelt in strofe 8 een rol. Enjoy ! Over de roos in de oudheid, zie hier.

Dick Wursten